How (Not) to Talk About Colourism

Keletso Mopai

I was shy in my teenage years when I discovered I am a dark-skinned girl. I was seventeen when I learnt the word colourism.

It is said that it was the writer and social activist, Alice Walker, who coined the word in 1982, over forty years ago. I have experienced colourism since I was a child. Even when my mother introduced me to strangers for the first time, someone mentioned something about my skin tone, the same way I always hear adults talk about dark-skinned babies.

Growing up, it was through interactions with Black children and adults that I was made aware of my place in society. No one prepared me how to deal with living in my skin and to see it as something that was beautiful, especially when you are constantly told otherwise.

To see yourself in another light is self-taught before you even begin to understand why such a thing is happening to you in the first place.

Although I experienced colourism, it was only when I joined social media that I met the word for the first time. Prior to this, my experience didn't seem like an issue that people talked about or advocated against, like racism. As someone who lives in South Africa, racism is the one social issue that I was introduced to through television and historical books, which impacted me and those I love tremendously. However, I’ve come to realise that while I am Black, being a dark-skinned Black woman is the identity that takes up so much space for who I am. A lot of my own joy and trauma stems from being a dark-skinned Black girl, not quite much being a black person.

To clarify, being Black is my currency and, on the other hand, a defect in the world, depending on the environment. While being dark-skinned has always and unflinchingly affected my entire being, humanity, and overall social life – interracially and intraracially.

Therefore, it is glaring to me when someone is being colourist just as much as (or even way more than) when they are being racist.

I often see the underlining meanings and messages that are quite offensive in our colourism discussions on social media, in our daily physical encounters, literature, etc, that someone who is Black but isn't dark-skinned might not notice.

There is a way in which people engage or talk about colourism that often leaves me unsatisfied, not thorough or whole-hearted, sometimes dismissively. It is moments like these that make me bitter. And because of this bitterness that I’ve harboured in the years since I found about myself, I feel I should explore the problematic ways we engage the colourism topic.

Social Media

One discussion that comes to my mind often occurred in February 2022 when nine African models were featured in British Vogue. Out of the nine, the four included were notable runway models (see the below picture) Adut Akech (front, left), Anok Yai (front, right), Diba Amaty (middle, right), and Akon Changkou (back, right). The picture was taken by Brazilian-born photographer, Rafael Pavarotti.

Sourced via Instagram @rafaelpavarotti_

In the photograph, the models are grouped in dark hue, and seem to be purposely dressed in black from head to toe. Their outfits and hair seek no attention in the photograph. Their skins appear glossy, stark and nakedly black, giving a homogenous guise. The background is brown (a rather subdued colour),and does not offer vibrance to the picture at all. It's as if the photographer went out of their way to make the photograph as black as possible.

I came across the photograph on Twitter as most people did. I was struck by it, as it was shared and retweeted, but perhaps for different reasons. For me, it wasn’t the noise that it was causing, the debate, disgust, or just utter disbelief from most Twitter users. It was how artistically different it was. So, the models in the photograph weren't what drew me to it. It was the photograph itself.

The criticism following the cover was more focused on the models and the need for them to look ‘appealing’ or photographed ‘better’ to accentuate their beauty.

Despite looking at the cover through a different lens, I was intrigued by this concept in high fashion photography of ‘bettering’ pictures. Because behind the discomfort that the picture brought, it seemed there was a general agreement and undertone that the models' skin needed to be lightened, which to me would have been gross, since the models themselves have dark-skin complexions and aren't light-skinned. Making them darker was more acceptable to me than making them lighter.

In fact, why this photograph is one of the most controversial to be on the cover of Vogue, is what makes it unique. Even though the dark skin of the models is intensified and doesn't correlate with the models’ ‘natural’ form, it is an art-piece.

I find the photograph well-done because black isn't a colour that is associated with visibility or being seen. Black isn't a commanding colour in photography when there isn't a backdrop of a bright primary colour like red or yellow. And yet, the cover achieves both without much effort from the models. The black colour is bold and declared. This, I believe, was what the photographer, Rafael Pavarotti, wanted to achieve. The photograph itself wasn't about highlighting the models’ features or pretty faces, it was about showing black as a colour. It was Black dressed in black.

Critics surrounding the release of the cover also suggested that the photographer fetishised the models' dark skin complexions, like how the West has constantly done with dark-skinned Africans, especially in the fashion industry. They also suggested that ‘better’ camera lighting would have exposed the models’ skin and features.

Yes, maybe there should have been if that was what the photographer was going for. However, from looking at Rafael Pavarotti's previous work and thereafter, the Vogue photograph is distinct from what he artistically seeks – colour. It's either the extreme of blackness, whiteness, or brightness, there is barely an in-between.

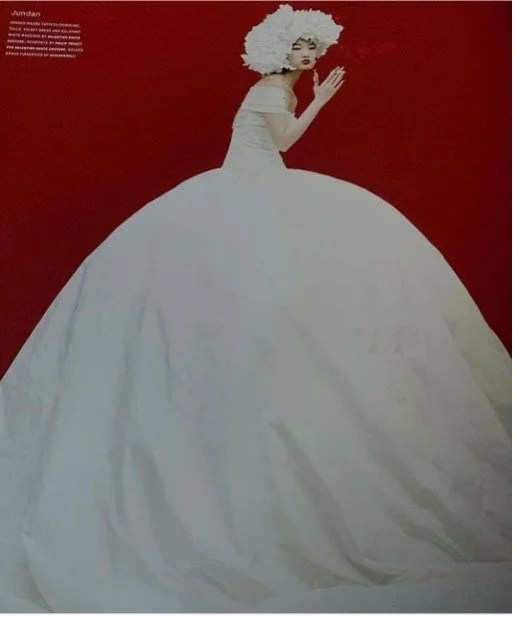

Sourced via Instagram @rafaelpavarotti_

Here is a picture of a model, Jundan Chen, taken by the same photographer for The Perfect Magazine, April 2021. The blood red background demonstrates the model's light skin and the voluminous white dress she wears. Her pose is simple and her stare is barely noticeable. It is the white garment, the white hair, and her light skin that makes the photo.

The photograph, like the former, attempts to showcase one colour – in this case: white. It's white dressed in white. And just like the former, the photo seems to do little with whiteness as a race but white – a colour.

The only difference between the two pictures is the background; one is dark (brown) while the other is bright (red). But there wasn't any controversy surrounding The Perfect Magazine’s photograph even though the model is Asian and not white.

The reason for this is obvious. White isn't the most prejudiced and scrutinised colour in the world, black is. Society links whiteness with purity and all good and godly things. But when we see black, we associate it with negatives, which brings discomfort, so much so that we want to change it, alter it, make it ‘better’ and ‘appealing’.

Black in art is a colour often used to showcase style, just as someone who says, “I like wearing black”, but it is rarely a celebrated colour. Black's history of Black people's brown bodies alone stirs anger and carries trauma, and perhaps this is why the response will never be the same.

Still, the models in both photographs depict the photographer's creative desire and vision, and a style that signifies his eye as an artist.

While I claim to see the photographer’s intents, I should also point out that the Vogue photograph is unrealistic, given our history. It would be hard to remove Black history or the models' humanity associated with being Black from the Vogue photograph, and that was the photographer's flaw. His imagination did not align with truth.

Blackness is too ostracised for it to be perceived as merely a colour. For example, below is a photograph of five of the nine models. It is the Black wearing black, red, yellow and pink. If one blocks the faces of the famous models, then perhaps you might see exactly that - colour wearing colour. Sadly, that would dehumanise the models and their blackness.

Sourced via Instagram @rafaelpavarotti_

Nevertheless, outside the bastardisation of blackness as a colour, we have to look deeper into ourselves and the type of language we use when we talk about dark-skinned Black people. We have to think about the implications of our anger when we look at the photograph. Why does it make us uncomfortable? Why do we think the photograph isn’t simply alluring and absolutely stunning? Using language such as that one Twitter user who said: “no one walks around looking like this,” with a tone that is doused in derision, says a lot about how conditioned we are into thinking Black isn’t beautiful.

The words we use, how we use them, reveal way more about what we believe. You may think you are advocating against colourism while in fact you are perpetuating it.

Society

It is true, that words can build or break someone. I can't count the many times I've heard someone call a dark-skinned person ugly without using the word. It is through phrases such as ‘dark as a night’, ‘midnight black’ or my personal favourite ‘black beauty’, since somehow a dark skin tone can't be just beautiful without attaching the word ‘beauty’ to it. That it has to be emphasised.

One would say that it is meant to be a compliment, but the truth is, it often has a bitter taste to it due to the fact that there is an exclusion within the phrasing, a box that only a number supposedly fits in, where not everyone who is dark-skinned can be called by this ‘black beauty’.

This reminds me of a discussion several years ago when a group of classmates or friends at the time, were paging through a magazine and laughing at how dark one particular Senegalese football player was.

Confused as to what the joke was and what it meant, I said to them, "But I am dark too," and one responded: "Not like him. You are not this dark."

I was dumbfounded, but it wasn’t the first time that a colourist comment left me speechless. I’ve heard a lot of backhanded and overt comments from friends and family growing up, so much so that when a long period passed without someone around me being colourist to me, it felt odd. I grew so used to it that I was always waiting to be emotionally bullied, and each time I waited it always came.

From the small comments such as “wear a hat or you could get even darker”, or “you don’t bath, your face is very dark”, and to the big ones where one tells you straight in your face: “you are so black, like a baboon”.

There were definitely emotional breakdowns and feelings of alienation, mostly in my teens. I avoided social interactions and I isolated myself. Getting out of the house meant another unsolicited remark from a stranger, which I didn’t know how to handle.

The anxiety continued for years, sometimes out of fear of going back to the helpless little girl I was, and other times I just preferred my little bubble of happiness without dealing with society’s ills. I couldn’t fathom how a Black person could see another Black person in that manner.

I later realised that racism has severely damaged the Black community to a point of self-hatred, where people see lighter skin as closer to whiteness and thus makes it ‘better’ because society made sure of it.

However, we need to start dealing with the problem we have perpetuated for too long. Black people continue to be colourists despite more knowledge, more textbooks, and more Google. And one of the reasons for this is just like racism serves white people, colourism serves those amongst us who are light-skinned . Because of this very reason, we are still here today, cutting corners, using ridiculous language and putting on a façade on social media in the name of activism.

But this is also what we are saying: that black isn't beautiful in all its entirety. That it isn't beautiful in certain faces, shades, or under certain lights. And what does it matter, really, if someone is innocently giving a compliment and calling me ‘Black Queen’ and I take it as an insult? Well, it matters to me that being dark-skinned is seen just as that – another skin in a world full of people who look different, not a skin with terms and conditions as to how it should look in order to be perceived as beautiful or appreciated. Not all dark-skinned people are beautiful, in the same way a white person can be seen as attractive or unattractive. If that description has nothing to do with their skin, then every Black person, whatever skin tone they possess, should be treated the same way.

Keletso Mopai is a South African writer and geologist. She studied for her MA in creative writing at The University of Cape Town. Her acclaimed debut collection of short stories If You Keep Digging, a social commentary on Post-Apartheid South Africa, was released in 2019. Keletso’s work is published internationally in several journals including Internazionale, The Johannesburg Review of Books, Kaleidoscope Magazine, and Catapult. In 2020 Mail & Guardian named her as one of the Top 200 Young South Africans. She was a writing fellow at The Johannesburg Institute of Advanced Studies in early 2024.