Poet, First and Last

Interview with K Satchidanandan

Asmaa Azaizeh

— —

Language as a theme and subject is strongly present in your poems. I’d like you to describe your relationship to language and how poetry shapes it?

You are right. A lot of critics have noticed this. Recently, a selection of my poems only on language was edited by a friend and brought out by a publisher. I have a long poem in my mother tongue, Malayalam. This engagement with language probably happens at three levels. Firstly, India is a multilingual society and you cannot find many Indians who are monolingual, even at the lowest level of society. So, we live amidst a thousand tongues, tribal speeches, dialects, slangs, languages and we keep translating from one to the other every moment of our life; as in several speech-contexts the person one addresses may be the speaker of a language different from one’s own and thinks in yet another. Secondly, as a writer, I keep engaging with language as meaning, image, symbol and metaphor, and many of my poems are direct products of this engagement. I give two examples ‘Stammer’ and ‘Cactus’.

Thirdly, poetry as an art consists of what the poet does with the language, whatever their themes and concerns are. Each poet is destined to find their own voice in a Babel of voices and this can be done only through the special ways in which their uses language in different poems. Each poem is also a linguistic discovery. In another sense, it is language that writes the poem through the poet.

You write both in your mother tongue Malayalam and in English. Is it spontaneous the way you go to either of them? Is it linked to a mode, a state of mind, or something else?

It is true I write in Malayalam and English, but I write poetry only in Malayalam; what you read in English are my own English translations of my Malayalam poems. I have translated 60-70% of my poems into English, but there are quite a few I have not dared translate as they are too local, have many references that only my people will understand, or the sound is an important element of the poem contributing to its atmosphere and even meaning and communication. But I do write prose in English, mainly on literature and at times on social issues, and have five books in English on Indian literature [and] eight books of my own poems in my English translation. Yes, India has a tradition of bilingual and even trilingual writers, mostly writing in their mother tongue and then in English, Hindi or Urdu. Kamala Das, who was also from Kerala, wrote fiction in Malayalam and poetry in English with equal ease and beauty. When I translate my own poetry, I do it like translating someone else taking the minimum freedom. I do translate other poets too, from Malayalam and Hindi and from English to Malayalam.

How do you link your political and social activism for a just and egalitarian society to your writing? How can literature and poetry be more effective in these hard times?

My activism mainly consists in delivering public talks, interviews, editing journals and writing columns. My political views are broadly Leftist though I have never joined any political party as that can be constraining to a writer as has been proved in many cases. I identify more with causes (social, environmental, feminist, LGBT, subaltern in general) and movements connected with them rather than with political parties and factions. I also do my bit for international causes as in the case of refugees and immigrants or cases like that of Palestine. Poetry or literature in general, may not be able to transform the world alone; but it can help raise awareness of issues and create empathy. We know the role literature has played in Arab revolutions, Black awareness, Feminist consciousness and anti-Fascist struggles. Poetry works not through direct appeal, but by shaping a counter-consciousness and creating its own special aesthetics in indirect ways. Your theme could well be love or death or language and even then, you can give them a new angle from your specific cultural and political context as Mahmoud Darwish had done or Najwan Darwish or younger poets like you are doing in Palestine. An address to your mother, a letter to your beloved or a poem on the felling of a tree can well be a political statement as well. Of course, it can at times be more direct too like the poems of Nizar Qabbani or Nazim Hikmet or Najet Adouani.

Czeslaw Milosz, the Polish poet once said: ‘In a room where people [unanimously] maintain a conspiracy of silence, one word of truth sounds like a pistol shot…’ And ‘You who have wronged a simple man / Bursting into laughter at the crime, […] Do not feel safe, the poet remembers. / You can kill one, but another is born. / The words are written down, the deed, the date.’ That is why I find Adorno’s statement about the impossibility of poetry after Auschwitz no more than an intense expression of anguish. We know the Nazi concentration camps produced a whole corpus of Holocaust poetry by scores of poets from Primo Levi and Paul Celan to Abba Kovner and Nelly Sachs. Only theirs was ‘a poetry for the horror-stricken, for those abandoned to butchery, for survivors, created out of a remnant of words, salvaged words, created out of uninteresting words from the great rubbish dump,’ to employ the words of Tadeusz Rozewicz. Pablo Neruda, in his 1935 manifesto, Towards an Impure Poetry explained his concept of (impure) poetry thus: ‘The used surfaces of things, the wear that hands have given to things, the air, tragic at times, pathetic at others, of such things, all lend a curious attractiveness to reality that we should not underestimate…’ In 1966, he again said, ‘I have always wanted the hands of people to be seen in my poetry…I have always preferred a poetry where the fingerprints show: a poetry of loam where the water can sing, a poetry of bread where everyone may eat.’ He dreamt of a poetry that carried the eternal stamp of humanity outside and inside every object, worn by constant use, full of smoke and sweat, food stains and shame, wrinkles, observations, dreams, prophecies, declarations of love and hatred, stupidities and shocks, doubts and denials, affirmations and celebrations, carrying the dust of distances, smelling of lilies and of piss, impure like a rag, like the body. Ocatvio Paz defined the poet as a man whose very being becomes one with his words and hence can make possible a new dialogue. I think there are lessons to be learnt from all of them for poets like us.

You are highly critical of the political situation in India. How does it impact your life and how does it make you feel about your motherland? Does it affect your writing about your place?

‘In the dark times, will there be singing?’ was asked of the German playwright-poet Bertolt Brecht once, and he replied: ‘Yes, there will be singing about the dark times.’ I would offer a post-script: ‘Poetry against the dark times too.’ James Joyce, too, was being affirmative when he said of writers: ‘Squeeze us, we are olives.’ The truth of his statement has been borne out time and again in the traumatic periods of varieties of Fascism, and totalitarianism of diverse hues. Poets from Paul Celan, Eugenio Montale, Federico Garcia Lorca, Miguel Hernandez, Pablo Neruda, Octavio Paz and Cesar Vallejo to WH Auden, Stephen Spender, Kim Chi Ha, Osip Mandelstam and Anna Akhmatova have responded to the horrors of Fascism and State authoritarianism. They were fully aware that silence before fascist onslaught was no less than acquiescence and collaboration in its monstrous project. I spoke at length about these poets of resistance only to highlight our situation in India where fascism of a new kind - for want of another word - is on the rise. It all began decades ago with the establishment of the Hindu Maha Sabha (The Great Hindu Assembly) that stood for the creation of a new kind of exclusivist Hinduism - up until then Hinduism had an inclusive outlook that even had atheist streams within it - by alienating Muslims as aggressors and foreigners. This created a lot of fear among the Indian Muslims, which was exploited by Mohammed Ali Jinnah (who was personally irreligious) leading to the division of India and the creation of Pakistan in 1947.

Since then, we have had several insular, militant Hindu organisations like the RSS that promoted this narrow-minded Hinduism that fed upon the hatred of other religions and promoted intolerance, thus shaking the very foundations of the Indian Constitution [which is] based on secular and socialist ideals. These forces also incited many riots, and committed massive genocides of Muslims, as [happened] in Gujarat in 2002; and in North East Delhi in 2020. Now it has found new patrons among the Corporations who contribute liberally to their funds and get a hefty return in the form of various privileges like tax exemptions, interest-free loans, which are often never paid back, causing the Indian economy to collapse. So, we have a monstrous combination of revivalist and capitalist forces that waded to power through blood and money, ruling India now with their absolutely anti-low-caste, anti-labour, anti-women and anti-peasant right-wing policies which are implemented with brute force. Some of us are still able to protest only because they have to maintain a semblance of democracy, though they do not tolerate opposition beyond a point. A brave journalist and three thinker-writers were murdered as they had interrogated the rulers’ theory and practice, while several right-wing leaders accused of murder or of making hate-speeches leading to violence are now members of parliament, and even ministers at the Centre and in many States. The many open democratic institutions meant to promote and develop science, history, arts, languages, literature and culture founded by Jawaharlal Nehru, our first Prime Minister, a scholar, writer and liberal, secular socialist, have been appropriated by these forces and turned into their propaganda machines. These rulers - who had no role in India’s struggle for freedom from the British, and had in fact betrayed it on many occasions - are now busy rewriting history, portraying themselves as champions of Nationalism and trying to erase the memory of Nehru and standing Gandhi - who had been murdered by a Hindu extremist as Gandhi upheld the amity and unity of all religions - on his head, portraying him as a champion of their poisonous brand of Hinduism, which they are finding hard to sell. Currently, they are also planning to drive away a section of Muslims by introducing a so-called National Register of Citizens, which will also impact a lot of India’s poor, of all religions, who may not have proper birth records; they have postponed its implementation only because of the spread of COVID-19 which has also put a temporary end to the people’s struggles against the Government’s draconian policies.

These developments are deeply disturbing for any free-thinking Indian citizen, not to speak of independent writers like me. We are trying to fight it through cultural organisations, artistic protests, online journals, newspaper columns, public discussions, festivals of resistance and, of course, through our own writing. It is impossible for any open-eyed writer today not to speak truth to power though many writers refuse to do so either out of complicity or of fear. I do not want to pretend I am a hero; I am just an ordinary man but as a writer I know it is my duty to resist this in every way I can, and I will continue to do it fearlessly as long as they let me live.

You’re known for your coinage of the term ‘pennezhuthu’ in reference to women's writing. I assume there is a lot to it. But can you illuminate maybe one aspect of it? How did you get to this term, or how does women’s writing differ from other writing?

I had used this term as a pure Malayalam translation of the French feminist expression, l’ecriture feminine (feminine writing) - the kind of writing where language is organised around the female body and desire, where patriarchy in every realm is questioned and gender-equality gets asserted, where women try to find a language - a ‘mother tongue’ - different from that of men where even grammar and ordinary expressions bear the stamp of patriarchy. I used the word in the introduction to the first short story collection of a Malayalam feminist writer, Sara Joseph, and it generated a lot of interesting discussion. In some sense, it was the beginning of the feminist critical discourse in Malayalam, though it was written by a man who considers himself half-woman! Look at this poem of mine titled ‘She inside me’ In fact, I have a bunch of poems which can be called properly ‘feminist.’

Even in the most painful images, your poetry seems like a safe lap, a low-voiced dialogue with the reader. You don’t throw pain in the face of the reader, you lead him to see it himself. Do you think of that while writing? Do you try to purify poetry from direct language?

I try not to shout or wail in my poetry. As far as possible I try to be indirect, speaking through images, metaphors, symbols. Yes, there are certain political contexts that force you to be more direct and then I do not shy away from that; but I am happier when I am indirect yet communicative. I use a lot of irony too in my poetry – that is another way of being indirect. I have often been asked to ‘define’ poetry and I always do it negatively: poetry is not fiction, not drama, not essay…and ultimately what differentiates these from one another is the way language is deployed.

You’ve gained international celebrity, with prizes and translations into many languages. As well as a huge number of books. What can you tell us about this dedication, and what is it in writing that gained your time and loyalty?

No one writes in order to be a celebrity. We write to express ourselves and our world, which also includes nature. I myself am surprised when someone from another language asks me whether she/he can translate some of them, or even a whole collection. They might have come across translations of my poems in English, to begin with. My books of poems in French and German and some of the Indian languages like Tamil, Telugu and Hindi were direct translations from Malayalam; the Italian translator came home and stayed with us to compare her drafts done from English with the original. The Arab translator did them from English but I got each poem compared in detail with the help of a Malayali friend who is a master of Arabic. The Irish, Chinese and Japanese books were done from English too. But what I gather from my experience is that poetry has a universal core despite the specificities of language and locale and that must be why readers of these disparate languages are able to connect themselves with my poetry. Maybe, as Walter Benjamin says, translation is a way of reinventing that common language of humanity that we are supposed to have had before Babel.

You write in different genres: poetry, short stories, and plays. Do you think that each genre accommodates a certain personal or literary condition? Why did poetry become primary?

I began as a poet and, I am sure, will end as one. Other things come to me as a surprise: I have been writing some stories only in the last two years as I felt some things are better said as fiction - though, as a French interviewer had observed, there is a strong narrative element or context in many of my poems, and my stories too have a lot of fantasy, irony, sarcasm and indirectness. I also wrote some ghazals - 50 of them, many of which have been set to music and sung by musicians - as they just came to me when I was taking rest after a surgery. They really took me by surprise. I adapted some plays by Brecht, W. B. Yeats, and Lady Gregory for the theatre when we had a People’s Cultural Forum in Kerala; later I wrote an original play on the last days of Gandhi and the partition of India for our ‘Indian Secular Forum.’ I entered criticism in order to introduce the new trends in poetry that some of us had pioneered in Malayalam; later I somehow became a critic and began to write about other genres too - fiction, drama, film, painting. Being involved in social movements, I could not but write social commentaries on a number of issues from education to liberation theology to environment; and all through I kept translating poetry from around the world: they come to around 2000 pages, done over fifty years. But yes, everything ultimately came from my engagement with poetry and if I am known at all in future, I would like to be known as a poet. Let me end with a few lines from your own poem ‘Reading Biographies of Prophets’:

Gentlemen, this is not a game.

This is infrared and ultraviolet.

Even acid cannot touch it.

We must be prophets

and madmen to see it.

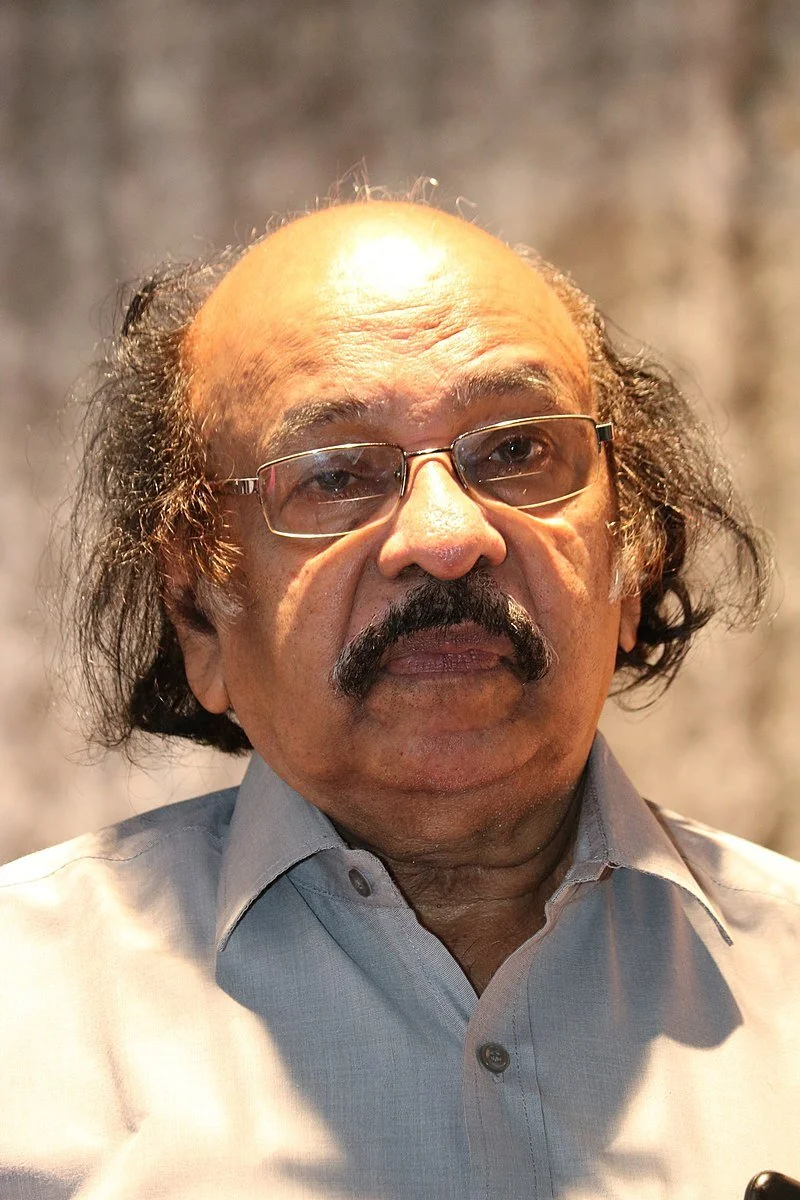

K Satchidanandan is a major Indian poet, with twenty-four collections of poetry to his credit, as well as several collections of world poetry in translation. The two primary languages he writes, speaks and thinks in are Malayalam and English. A fearless voice against oppression of all kinds, his many public roles have included being Director of the School of Translation Studies, IGNOU, Delhi, and National Fellow at the Indian Institute of Advanced Studies, Shimla. Photo by Kannan Shanmugam.

Asmaa Azaizeh is a poet, essayist, and cultural manager based in Haifa. She has published three volumes of poetry - the award-wining debut collection Liwa (2011); As the Woman from Lad Bore Me (2015) and Don’t Believe Me If I Talk of War (2019), which have appeared in the original Arabic as well as in Dutch and Swedish versions. She was the first director of the Mahmoud Darwish Museum in Ramallah and has worked as a TV and radio presenter. Photo by Dirk Skiba.