The Child Within

A conversation with Alf Taylor and Dennis Haskell

Warning: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers should be aware that this interview is with a person who has since passed away.

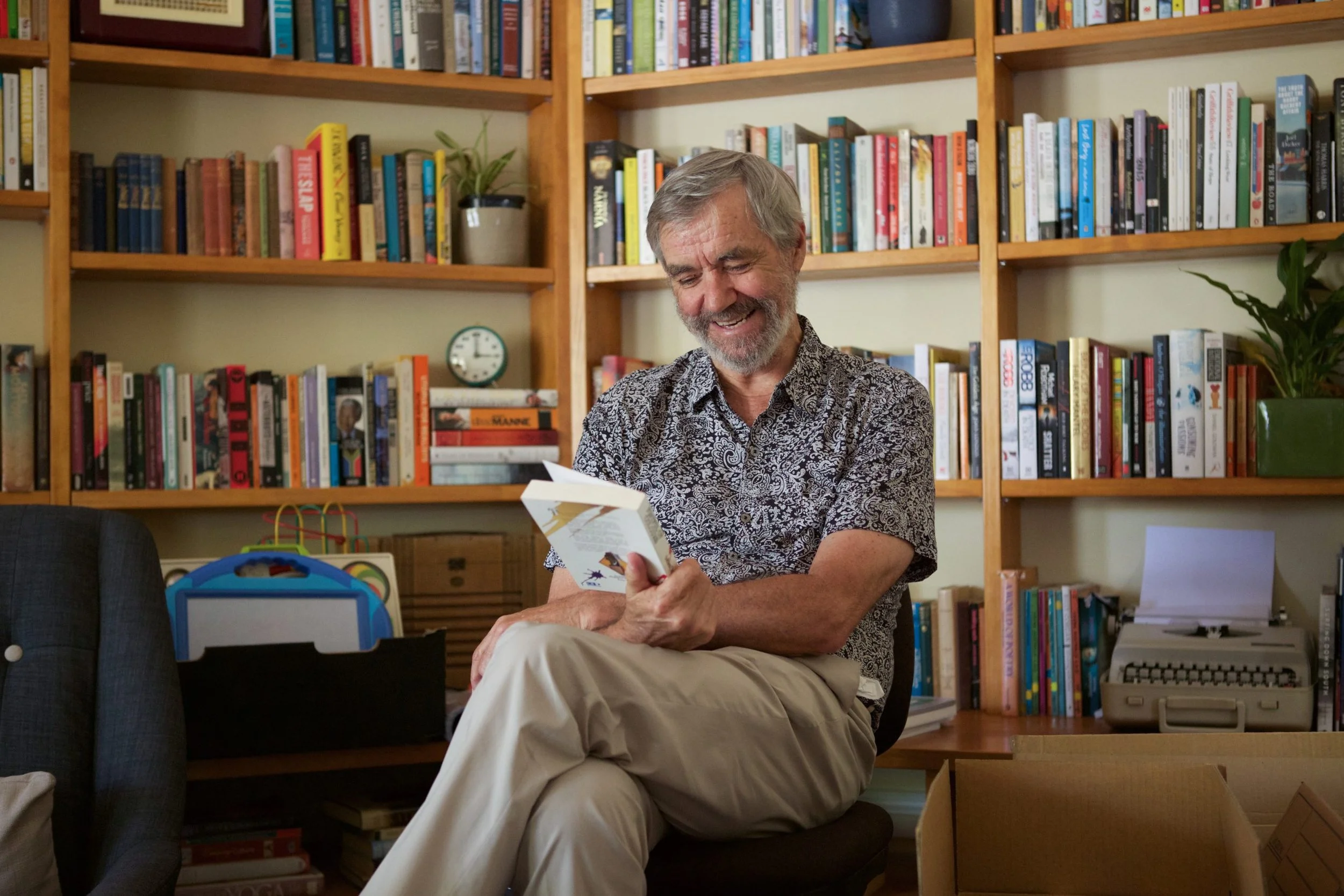

Uncle Alf Taylor’s memoir called God, the Devil and Me was published in March 2021. It represents over 20 years of work for Alf, and 16 years of work for Dennis Haskell, who has edited the book. On 28 January 2021, Dennis and Alf sat down to talk at the Centre for Stories in Boorloo/Perth, ahead of the book’s launch.

— —

Dennis Haskell: Alf, you've published poems and short stories before but this is the first time you've published a memoir. Did it feel different to write?

Alf Taylor: I guess it… it did come easier to the other books I've written; it’s closer to the heart. The others, the stories and poems, were my own creation.

Dennis: Did that make it easier or harder to write?

Alf: That's a good question. Yeah, a little bit of both I think.

Dennis: What made it easier, the fact that it was your own experience, so you knew it already?

Alf: Yeah. Yeah. But the trouble was, the words had to relive the child again! The only way I could ease some of the pain from within was through writing the child, who sort of wasn’t me. I got him alone, I said, right, you're my hero. You show me your life, then I'll write about you, not about me.

Dennis: For people who haven't read the book yet, can you tell them what it is about, the part of your life that it's really about

Alf: It's, I dunno, it's about missing…missing my Mum and Dad. That was the number one hurt.

Dennis: So, it's from when you're about five years old.

Alf: Yeah. Something around that age bracket, yeah. And missing Mum and Dad, that hurt the most.

Dennis: At the age of around five, you went into New Norcia Mission.

Alf: Yeah, I went, went in there and I remember waking up that first morning and I actually thought I woke up in Hell. I see all these monks and nuns around me. And they all had these black habits on. It was so scary. Aaaahh! And I thought, if this is the life I've gotta live, I'd rather be dead!

Dennis: Did you feel you got much of an education in New Norcia or not?

Alf: No! There was no education at all from the start. I remember when we first went in, Brother Aldephonsus, he had the Mission red Chevrolet truck; he used to pick all us boys up. I remember this morning, it was freezing cold. We all had to go out and clear the paddocks, pick up the sticks and stones, and put them into a heap so they can bring the tractors in to plant the crops.

Dennis: Well, it gets cold at New Norcia.

Alf: It did yeah!

Dennis: And did you have your own clothes?

Alf: We had a pair of shorts and shirt, that was it. And in winter we just had a jacket, a khaki summer jacket, nothing on your feet,

Dennis: Even in winter?

Alf: Yeah. The stone bruises, they were the worst. Even thinkin’ about them now, uuggh, I want to lift up my feet to check. But I remember eventually we did go to school. We all used to walk in line to the Girls House where we went to school, and the Spanish nuns who taught us, they spoke very little English.

Dennis: Oh really?

Alf: And that way I think they were learning from us in English or Noongar or whatever we were talking, and yeah, it was scary.

Dennis: Well, one of the things that was difficult for you was the language that you weren't allowed to speak: Noongar.

Alf: I remember Father Basil got all us little boys around, and he said to us: ‘If any of you speak in your Aboriginal tongue or speak about your Aboriginal culture, God is coming down from Heaven and sending you to Hell, where you'll never see your mother or father again: it's a mortal sin!’ A mortal sin in the Catholic dictionary is the worst sin you could ever commit.

Dennis: So you learned some Latin instead of Noongar?

Alf: I learnt the Latin to say mass and I think I was talking Spanish too for a while.

Dennis: And how then did you come to write?

Alf: I think I was always meant to become a writer because it was just in me. The only thing I learned was like, when I had a pencil in my hand I felt I wasn't the typical little boy who was going to school, timidly creeping around. It made me something bigger than what I was. And what saved me, I think was…I was very young and I stole this book. It was titled Dick and Dora. And I forced myself upon Dick and Dora, then I learned how to read a little bit. You know, once I learned to read, I started to scribble my name, which made me pretty high up in my bracket of age groups. That started me: Dick and Dora.

Dennis: Apart from Dick and Dora, one other fellow I know was important to you, and that was Mr. Shakespeare.

Alf: [Laughs] Ah, I know I fell in love with him, when I was about 8 or 9. Sister Angeline used to call us ‘little black devils’ and tell us, ‘You're never gonna make it in life. You're going to drink yourself to death at a very early age.’ And I used to say ‘Yes, Sister, I’m going to do all that,’ you know, because you believed in what the Sister told you. But one good thing, they used to have a library in the back of the class and when this ugly little black devil went into the library and looked at books…You know, my little heart would go boom, boom, boom, boom. It was fantastic to look at a book. And I looked around and I saw this painting or drawing of this author, and he would have to be the ugliest painting or drawing I ever saw. And I said, okay, he's ugly, I'm ugly, we’ve got to be related! We’d have these books and, like I said, I loved how he put words together and, and I'm thinking to myself, I want to write like him! This ugly feller was William Shakespeare.

Dennis: And much later on as an adult, you managed to go to Stratford.

Alf: Yeah, I did. I mean, it was fantastic when they invited me over there and I visited where he lived and I think where his missus lived, and I went through all the houses that he lived in, and it didn't cost me a cent once they found out that I fell in love with Shakespeare at a very early age.

Dennis: You mentioned the child. Can you talk about the child? The child was someone not you, kind of you, but not you.

Alf: Sort of well, like I said separating myself from the child was very hard for a start. Because with the child, I…Alcohol, drugs, pills and everything, it was all there because I couldn't live with the ache within me, while writing this book. And so what I did, I got together and I separated myself from the child, but I said, look, you show me your life in New Norcia, you will be my hero. I will write about you, not me. And that's where I found that words came out much easier. And even, you know, the apostles, they were all dumbos themselves!

Dennis: There's also mention in the book of Toby as an important character. Can you talk about Toby and how he's related to the child?

Alf: Well, he was, I think Toby was bigger than the child, you know, he was there with me when I first went into the Mission. Oh, yeah, that's right. We went out in the bush one day and inside my head someone was talking to me, and I looked around and I couldn't see anyone there. It's a creation inside your head.

Dennis: So he was your imaginary friend. And he becomes an imaginary friend of the child.

Alf: He did. Yeah. Yeah. And I tell you what, he helped the child out in a lot of difficult situations.

Dennis: So that helped you. That was the way you coped with the punishments and the hard life in New Norcia. And then you remembered it when you came to write?

Alf: I did. Yeah. It's…you know, you tried all this stuff you received as a child. You want to get rid of it. No, I don't want to, I don't want to live that life again. And then, you know, you got people like Toby come back and they remind you of your life. And then bang, you jump into that ditch, and off you go.

Dennis: You had some other heroes while you were in New Norcia. I know Michelangelo was one.

Alf: He was, he was fantastic, Michelangelo. I mean, that was because the Spanish people brought him over here. I don't think Australian people would have had Michelangelo, but they had these books and I used to read about his sculpture and painting on the wall. And, well, he was another bloke I wanted to be like. And I often thought to myself, I used to tell Toby, if I can get a hammer, I’ll go and find the biggest rock and chisel away. I might've had a hard time.

Dennis: And your other heroes I know of, well General Franco was a hero…

Alf: It was amazing in there, because Brother Augustine… they dumped all this Spanish culture onto us. So I wanted to fight in General Franco’s army when I was 12 or 13, because in there we'd never heard of Hitler. I never learnt of Hitler until I got out.

Dennis: The other bit of Spanish culture I know that you aspired to were the bullfighters.

Alf: The matadors! I used to ask Brother Ian, but he used to tell me how these matadors - long before we saw any of the matadors - you know, they used to tell us how they used to fight this great big bull, boom, and then kill the bull at the end. And then take a rose and give it to the prettiest señorita there. And I wanted to do that. When I went to Barcelona they took me to a big bullring there. They said it was all shut down.

Dennis: I think it's banned in Barcelona now.

Alf: Yeah, it is.

Dennis: But in other parts of Spain, they still do it. It’s pretty brutal though. So this is when you're a young kid, you wanted to be like Shakespeare and Michelangelo and a matador, but you're in New Norcia till you're 15 or so: you went to the Girls School; did you ever see the girls there? Were there Aboriginal girls there?

Alf: The boys went to the Boys House and the girls to the Girls House. They stayed at St. Mary's orphanage; we stayed at St. Joseph's orphanage. ‘Orphanage,’ but we all had mums and dads. The government at that particular time said that we were all orphaned, and encouraged the missionaries from overseas to come over here to Australia and they paid them the child endowment money and never wouldn't pay it to the Aboriginal mothers. The monks and nuns made a lot of money out of the Aboriginal kids.

Dennis: And did it make you believe in God and the Devil?

Alf: Yeah, I did! I, I believed in God, you know, I didn't want nothing to do with the devil. Now I reckon I’d be safer with him than anyone else; some of my life friends are there.

Dennis: When did you stop believing in God and the devil, or at least the monks’ Spanish version, after you got out of New Norcia or…?

Alf: It took a while for me to really, you know, because I still deep inside me had that New Norcia upbringing. It was a bit hard.

Dennis: They say Catholicism is one religion you can never leave.

Alf: Yeah. It took me a while. And then I thought…it wasn't long though, after I got out, I said, right, you are the church, you are the steeple. I said, you fall down, you got to get up and you got to do it yourself. You make a mistake. You've got to try to improve, not to make a mistake again, so that I was the church.

Dennis: So it's about 15 when you got out of there, and the book recounts a bit about getting out. You could tell a little of that story because you weren't released.

Alf: No, no, no, because they tried to keep you in as long as possible. But when my old nephew or cousin, Nunhead came up to me and he said, ‘Come on, let's run away.’ And I recall that time we were in the Mission we were taught more of England - Mother England I should say - than this country of Australia. And he said to me, ‘Let's run away because they won’t get paid for keeping us anymore.’ And he said, ‘Let's go and save Robin Hood and the seven thieves.’

Dennis: So you escaped and you got to Perth. And you went looking for your Mum?

Alf: Yeah. We come down to Guildford. There was a little reserve or a street down there called Allawah Grove and we stopped in there. They moved it from nine o'clock in the morning, yeah, they were allowed out from nine o'clock to six. If they got caught out there before nine or after six, they would give them three months in Fremantle prison, Aboriginal people, you know, that was normal. That was the Government. That was the law.

Dennis: And did you know at that time that your Mum was still alive or did you think she was dead?

Alf: I had a fair idea that she was alive; but at that particular time, she used to tell me that if she wanted to come and see me, then she had to get a pass. She wanted to try to see me once. Aboriginal people had to get a pass to travel. And when they got up to that destination, they’d show the police who they were and that, so the police wouldn't pick them up and put them inside for vagrancy.

Dennis: Just like living under General Franco.

Alf: [Laughs] I found out via Hitler! But when I get told to Allawah Grove and I told them my name and my mother's name, they said she's in Merredin. So somebody gave me two bob, but those days two bob was, wow…So I caught, caught a train from Guildford to Midland, and from Midland walked up Great Eastern Highway, to Greenmount. That particular time, there wasn’t many houses around. And from there I hitchhiked to Merredin. And I got to Merredin, and camped at the waiting room there where the trains come through, you know, to fill up for coal; and I camped the night there and then got up early in the morning. And that’s right, walking around Merredin, I met some Noongars there, and one said, ‘Who you lookin’ for?’ I told him, gave him my mother's name and he said, ‘Oh, she was here but she just gone through to Coolgardie.’

Dennis: That's near her country.

Alf: Yeah. She was in her own country. All her people were there.

Dennis: You were 15 or 16 at this time?

Alf: I think I was pushing 16…because the Beatles were coming out and they would take over the music, well anyway take over the Australian music world. I hitchhiked from Merredin and I got picked up by this pastor and his daughter. I'll never forget them.

Dennis: You describe them in the book. But I wonder if they'll recognise themselves.

Alf: Hopefully they're still alive.

Dennis: Well, daughter would be, I imagine.

Alf: Yeah, I reckon. Yeah.

Dennis: So, you did meet your mother, and I know that meant a lot.

Alf: It did! But the worst thing, when I came within walking distance, talking distance, should I say, she looked at me and she said, ‘Who are you?’ I knew who she was.

Dennis: How come you knew her - you wouldn't have seen her for 10, 11 years?

Alf: I dunno how, it's just, I knew it was her. I remember the little hats she used to wear.

Dennis: Did you look like her or not?

Alf: I just knew it was her!

Dennis: But do you look like her or look like your dad?

Alf: More like Mum. And, I looked at her and when she said ‘Who you?’ that to me was like being smashed across the face. Then I told her, I said, ‘Abby!,’ because I remembered, and that's the only way I had her, when I said ‘Abby.’

Dennis: And others wouldn't have known your child name. So you didn't find your brother, you didn't find Ben at that time.

Alf: No, no, I didn't. But there's another brother, Tony, but he was married and he was living somewhere in the wheat belt area.

Dennis: Right. So near Merredin?

Alf: Yeah, just down from there: Kellerberrin. You know, but…I looked at the land they were forced to live on, you know, the reserve, desolate, I wouldn't even have buried Hitler there.

Dennis: The other thing that's in the book is very different. The book ends with this Monty Python-like imagination.

Alf: [Laughs] I reckon that Monty Python was true! I still believe that!

Dennis: [Laughs] So in this part you go up to Heaven and you meet some apostles and Judas Iscariot.

Alf: Judas Iscariot becomes a good mate of mine. He was fantastic! And he told me that none of them, the disciples Jesus Christ tried, they didn't ever have an education. The only ones who had an education were the rich people, you know, the kings and the queens and so on.

Dennis: It's pretty right! At the time that was true.

Alf: The parents, when Jesus started talking in parables, they were sort of mystified. Wow! They listened to these parables coming out, and Judas told me that, you know, you get about three or 4,000 at one of these meetings and they'd all be dropping in copper or silver. And back at those days, whoa, that was a lot of money.

Dennis: That was more than two bob! [They laugh.] Where, where does that come from? You write this fantastic stuff, which is very funny, like an alternative version of the Bible, a Monty Python version of the Bible.

Alf: Exactly. But it came to me so clearly. When I was sitting down writing this I could actually see - what's his name? - Peter. When they tried to hang, Judas, ah, you know, I could actually feel the cold air of Galilee, and see them looking over this valley.

Dennis: Well, it's very funny. And one of the great things about all your writing in the poems and the stories and the memoir is just humour, a lot of it. And everyone says how funny it is.

Alf: Yeah. I'm sure that New Norcia gave all that to me, because I seen boys got a flogging, bare bum, back, legs, with the strap. You know, you can actually see when the strap makes contact with the skin and the skin opens up and all the fluid runs out of there, out of the breaking of the skin…You know, you want to cry for this boy and he's there and you’re glad to go and support him, but the tradition in those days was if you go and say ‘Don't cry,’ you’d get a flogging yourself. So you're looking at him with a lot of the boys there, and he’d look at you and his tears coming out of his face, and he'd look at you and then he'd point at your face, and he’d start laughing. ‘What are you laughin’ at?’ ‘I'm laughing at your face because you're the ones who anyone’d think you just got a floggin’, not me!’ And I thought about that and I said, I can do this whatever way I want to do, with humour.

Dennis: It's black humour. The humour is mixed up with, with tears, with suffering. A lot of the time you laugh and then you think, what am I laughing at?

Alf: I know, I know, this is terrible!

Dennis: Well, this fantastical kind of imagination comes through more in the memoir even than in the stories and the poems. I think that's unique in Aboriginal writing. That's quite striking. And I guess it's just part of you.

Alf: Yeah, it does. And it is. And I must add, you too. Thank you, Professor Dennis Haskell.

Dennis: Well, I got involved most of all, when I knew you were writing and it was so painful you couldn't bear to re-read in order to edit it. And you wrote it in these sections, these fragments in a way: it's not start here at section 5 and end up at 15, it keeps going around to something, and then it goes away and comes back.

Alf: Yeah, that well, that's the only way I could write it at that time. Because like I said, the child was within, and he was the one crying and hurting, and it made me cry.

Dennis: Well, I think it works because it shows that that child is still part of you. It seems those memories are still part of you. I know it's a story about the past - of course it must be in a memoir - but a lot of that past is still present for you, I think. Do you agree? Do you think that past isn't just past, it's still part of you?

Alf: Yeah, true. Yeah. It's, it's still within because now it's sorta…when I was writing it, I had to write all these other books to get away from that hurt, you know, create some humour in Long Time Now, write the poems and then go back.

Dennis: I think that now it's written - here’s the book of God, the Devil, and Me - that's cleared it out for you a lot, that you’re kind of okay with it now? You’re certainly good talking about it.

Alf: Yeah. Yeah. I feel, you know, I, well, I'm actually glad it's out; but I don't want to throw the child away.

Dennis: Yes. I have this theory that creative people have the child part of themselves stay much longer than other people.

Alf: I don't want to get rid of him!

Dennis: Well you probably can’t! And what do you feel about the Catholic church now? And the monks and New Norcia?

Alf: I told someone, I just can't stand this, well, particularly the Catholic church. Yeah. I can't stand the Christian religion. I hate it. I hate what they did to me.

Dennis: Yeah, sure. They have tried to change in recent years with all the stuff coming out about paedophilia, but still I can understand your feeling like that. Maybe I can just ask, what do you look forward to writing now? You're still writing.

Alf: I want to get onto Alliwah Boolyaka Nidja. I want to start on that. And, but like you said, at the moment, I'm talking about God, the Devil.

Dennis: And Singer Songwriter and Long Time Now…

Alf: Yeah. I want to settle down and just sit on that. I'll tell you what, that's gonna be bigger than John Lennon.

Dennis: What's it going to be? Do you want to tell us about the book?

Alf: Well, I'm going to write about what happened in Australia during the fifties, you know, because in that particular time, if you were a fair-skinned Aboriginal child they could come and grab you, take you to a police station. You know, bounty hunters, kidnappers, they can take you to the police station, and the sergeant would come out from behind the desk, grab your hands, look at the colour of your skin, put you in a cell, and he’d come back and write out a receipt for pounds, shillings and pence, depending on how young the child was, I suppose. And he'd write out and give it to the bounty hunter, who'd go with his cheque to the bank, cash it, and could take his girlfriend out to a lovely meal.

Dennis: You write about this in your mother's story; we published a little bit in Westerly.

Alf: Yeah. Mum's story that, that was fantastic. You said about a hundred pages were cut from the manuscript of God, the Devil. But you said that it'll be all right for the new book, especially If we can get some photos.

Dennis: I think so. Will the new book have anything about your army days? Because you were in the army and that was in some ways good for you, although it taught you drinking. There's none of that in God, the Devil because it happens after.

Alf: Yeah. In 1970. I was called up for national service.

Dennis: In the ballot.

Alf: Yeah. It said, ‘You are to report down in Fremantle.’ I walked in and they said ‘Congratulations, you won the lottery! You’re in the army now.’

Dennis: In some ways it was a good experience for you?

Alf: It was, it was. Because when I first went in there was a lot of little white guys that came, you know, still from their mothers’ apron strings. And they couldn't handle all this vile language they were using on you to turn you into a man. That's what they do. But I was already a man before I went in.

Dennis: It was just like New Norcia again!

Alf: Well, language didn't affect me. Some of the filthy names they used bothered me, but I said ‘Yes, sir,’ ‘No sir,’ ‘Three bags full, sir!’

Dennis: You were used to the discipline.

Alf: Exactly! Wake up, get up in the morning, ready to go after the day. They call your name out…‘Where’s so-and-so?’ You’d look in the bed…‘Ah, he’s probably gone back to his mother.’ This is what the old sergeant says, or the corporal…

Dennis: So, you were already toughened up?

Alf: Sorta, you know. But a lot of the boys I went through New Norcia with drank themselves to death. I mean they went in as little Aboriginal boys and then had the Spanish culture dumped upon them. When they got out, they tried to go back to the Aboriginal families but they’d find that they didn't know who they were. They just drank themselves to death. And I, you know, I'd like, I'd like to dedicate this interview to the boys I went to school with.

Dennis: As the book is.

Alf: Yeah.

Dennis: But you had to get through that yourself. You know, after the army or in the army, they taught you to drink and…

Alf: [Laughs] I mean, you go, there's about 50 cents for a stubby, Carlton draft or XXXX in Queensland, 50 cents - cheap over there. And a good bottle of scotch, that was only about $5. Most of those boys who I went into the army with, they're all wiped out. Even these white boys, you know. I went through with both black and white boys.

Dennis: Did you get much racism in the army?

Alf: No, no! Oh yeah, once. But it wasn’t directed at me, it was at a mate who was in the same platoon I was in; and this bloke, he called him ‘a black n*****’ or something. And then instead of the black fella jump up and flog him, all the white boys jumped up and nearly killed him! Me and the bloke who was taunted, we had to grab all these white boys and pull them off!

Dennis: A good story, Alf, that's interesting.

Alf: They would have killed him!

Dennis: You had to get through the drinking issue yourself.

Alf: Yeah. Well Ben helped a lot.

Dennis: This is your brother. Ben. Who'd been through it already.

Alf: Yeah. He went through it all. He could see me, and thought, ‘This is not going to happen to him.’ But you know, talking about all this now, it's sorta, well, did I actually live through all that?

Dennis: You can write about that in the new book, that's good subject matter!

Alf: It’s all going to come out! I wrote one about the army. That was when my daughter was born in Townsville. [‘The Best Night of My Life’ in Long Time Now].

Dennis: It's a lovely story.

Alf: I’ll probably get some more stories: I want the matador to come out, General Franco, what else? I want to put all these in together. Last night I thought about this: in Heaven this Nazi, they caught him with a black Jewish girl.

Dennis: This is the story you’ve started to write.

Alf: Yeah. He went and shot a superior officer - he was a young officer and he let this black Jewish girl live, and they both came over here and they, where shall I send them to? She came over as a nun, and he came over as a priest - he had to disguise himself. And he'd done such a good job, well, they both did did such a good job that all the Noongars wanted them, so they wrote to the Pope and said that we want to turn them into saints. The Pope agreed with them, and they went to Heaven!

Dennis: That's a good story and a good note to end on. Thanks a lot Alf!

Alf: Thank you Dennis!

Alf Taylor is a leading Noongar writer who has published poetry and short stories, and has now branched out into memoir with God, the Devil, and Me. Alf says that when younger he would have most preferred mermaids but he's more a bush person.

Dennis Haskell is a Wadjela/white poet and literary essayist, who worked with Alf on the book for some 16 years. He loves the sea and its creatures, especially seahorses and stringrays.