How the Gond art transformed from rock-mud-walls to canvas

Madhavi Uike

Translated by Chandresh Meravi

On 11 November 2019, the multinational mining conglomerate Adani group organised an exhibition titled ‘Gondwana’ in their headquarter in Ahmedabad, where two artists from Australian Aboriginal communities, Otto Jungarrayi Sims and Patrick Japangardi Williams, were invited to India to collaborate with the Pardhan-Gond artist, Bhajju Shyam. This was a strategic move by the Adani group, which is facing severe resistance from the Aboriginal communities in Australia and Koitur people in India for extracting mineral resources from their indigenous ancestral territories. The term Gondwana refers to the region considered as ancestral territory of Koitur people, who are also identified by the Indian state as Gond or Koya people. Gondwana roughly comprises of former Central Province and Berar (under British colonial rule) and is now divided in six different states – Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Telangana, Odisha, and Uttar Pradesh.

The practice of depicting everyday life, culture and histories on the cave rocks was one of the most ancient practices of the Indigenous peoples across the world. In central India’s Gondwana region, the Koitur or Gond people have been practicing rock art in caves and outside the walls of their houses for generations. After decades of transformation, these art practices have taken new forms in paintings and canvases, and become one of the most notable Indigenous art forms of India. The Adivasi or Indigenous art forms in India such as Pithora art, Warli art, Bhil art and Gond art are not merely combinations of colour and pictures, but it also depicts literature and history of the people in a certain time period. In the context of Gond art, for instance, the Gond paintings represent unique Indigenous philosophy, origin story, and histories.

The genealogy of Gond art goes back to many generations, where art and murals were drawn on walls of houses using materials such as – leaves, trees, bark, red-yellow-black coloured soil, limestone, cow dung, flowers and so on. These wall and floor paintings are called as bhitti chitra and dhigna art. According to community elders, the idea behind building these arts on walls was to decorate houses and to also ward off evil spirits. Bhitti chitra, a form of wall paintings done using mud, cow dung, and natural colours, and dhingana art, the traditional art of wall paintings by Pardhan-Gond people, used natural objects to visually express themselves. The Pardhan artist and author Venkat Raman Shyam told me that ‘the word bhit means wall, while bhitti also means inside, thus Bhitti Chitra is wall painting, a type of mural painting especially done among Adivasi communities such as Bhil, Koitur and Warli communities.’ The Dhingana art, according to Venkat, is done on floors of the house. ‘In older times, it was done using colours from plant leaves (bush or kidney beans leaves) or flowers (palash or butea momosperma), red and yellow soil (ochre), limestone, cow dung, charcoal, wood ash and so on.’ He added that besides making the houses beautiful, the art ‘paid tributes to their ancestral spirits’. Similarly, tattoos can be considered one of the first art forms practiced by the Adivasi communities. According to Koitur creation stories narrated by the Pardhan people, right after the first male and first female –Naga Baiga and Naga Baigin – was created, the Baiga women started Godna (tattoo) on their foreheads and rest of the body as she did not go in front of bada dev without clothes. They were ordered to manage all life forms on earth.

Describing the transformation of the Gond art over years, Roma Chatterjee, a professor of Sociology at University of Delhi, in her book Speaking with Pictures argues that, according to Swaminathan, birds, mountains, or trees no longer “served to represent the manifest world of physical reality but became symbols of the human psyche.” She adds, ‘Gond art is a form that emerged self-consciously in the precinct of a modern institution, Bharat Bhawan, at a time when modern art the world over was questioning its European Legacy. It was through the so-called primitive arts – the arts of marginal cultures – that an alternative genealogy for modernist abstraction was sought.’

In 1981, Gond painting was first used on canvas by Jangarh Singh Shyam, a Pardhan-Gond artist from Madhya Pradesh’s Patan. Pardhan-Gond people are part of the larger Koitur community and have historically been considered the bards, carriers of oral histories of Koitur people, as they sang songs about Gondwana’s history and practiced visual art form in their walls. Shyam was brought to Bhopal’s Bharat Bhawan by the Brahmin artist Jagdish Swami Nathan. Shyam became the most influential Gond artist of the generation and his art travelled across many countries. In 2001, while Shyam was at a residency fellowship in Japan’s Mithila Museum, he died by suicide. His death still remains a mystery for many, as Shyam was at the peak of his artistic career. After his death, Gond art was taken forward by his family members. Currently, Anand Shyam, Venkat Raman Shyam, Bhajju Shyam, Japani Shyam, Roshni Vyam, among others are the contemporary Gond artists, whose works have brought global recognition to Gondi paintings.

The contemporary Gond paintings on canvas primarily use dot-painting technique. The practice is believed to have been derived from the traditional practice in bhitti chitra (mural art) and Godna art (tattoos done by Adivasi communities). Similarly, the dot-painting technique on canvas used by Australian Aboriginal painters also emerged in the early 1970s as Aboriginal communities worked with a white schoolteacher, Geoffrey Bardon. The dot-painting technique however was traditionally used by the aboriginal communities drew sacred designs for ceremonies and the body paint used by them used circles and dots.

According to Venkat, dot means ‘the starting point of the beginning or life’. He recalled that once when Swaminathan asked Jangarh to draw pictures of gods and goddesses they considered sacred, Jangarh drew a Bana – an indigenous string instrument – and a Saja tree on canvas. When Swaminathan asked him what it was and where were the gods, Jangarh replied, ‘we worship bada dev, who cannot be seen and doesn’t have a figure or statue, and resides in every element of life.’ In Koitur community, Saja tree is considered the residence of persa pen or bada dev, who is worshipped by playing bana. Roma Chatterjee writes that, ‘Jangarh’s gods did not look human and it is thought that the interlocking lines and arabesques were inspired by the designs that were used to decorate Pardhan village homes. It also gave his figures an air of mystery that appealed to the sophisticated urban audience.’

Besides wall paintings, there is an age-old practice of wood carving among the Koitur Gond people. Wood carving can be seen in the sacred wooden pillar used during the wedding ceremonies. Similarly, wooden memory pillars are built for deceased persons in various parts of Bastar, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Telangana. Similarly, Dhokra art form of Bastar uses metal carving to depict Koitur religious and cultural symbols. In many ways, the contemporary Gond art is an extension of various art forms produced by the community for generations. The wall paintings, just like the Bhitti Chitra – Bhimbetka cave paintings (which are considered as art-form of ancestors by the Koitur people) carry with them religious, cultural, and other symbolisms. These symbolisms, such as sacred trees, animals, and other beings, are reproduced again in the contemporary canvas paintings.

In Gond paintings, every human or non-living being is depicted as a living being or as part of nature. Even modern objects are depicted as trees, animals – suggesting that nature is central to these paintings. This is mere reflection of Adivasi social reality, wherein Adivasi life cannot be imagined without trees, forests, animals, and their natural surroundings. This natural world is also an integral part of Adivasi belief systems. In Koitur community, its 750 plus clans are expected to take special care of one plant and one animal totem of their respective clan. This means at least 1500 different trees and animals, which not only constitute a religious and ceremonial element but are also linked to birth-wedding-death cycle of the community. Additionally, trees such as Mahua and Saja are considered sacred by the community, and their imagery can be easily found in Gond paintings. Similarly, the bhitti chitra and Dhingana art does not only decorate the walls, but also is a way of paying respect to Adivasi deities and ancestors. In this manner, Gond painting also represents the Indigenous belief system practiced by the Gond community. Hence, another parallel that can be drawn between the Aboriginal and Gond art is how they portray their respective religious and cultural beliefs.

It is a common sight for Adivasi communities doing wall paintings, while singing folk songs. These folk songs are a crucial source of oral history of communities and narrate many folk stories, which are then again reproduced in paintings. These folklores are not merely for entertainment purposes but carry with them a vast knowledge of community’s history, indigenous knowledge, rituals and so on. Pardhan community, as mentioned earlier, were traditionally the bards of Koitur people, who travelled to far villages and sang songs narrating history of Koitur people, origin story, and other forms of oral history. The arrival of Bharat Bhavan and Jangarh Shyam, therefore also meant a significant shift of Pardhan-Gond community from music and songs to visual art.

The contemporary Gond painting mostly carries natural imagery such as trees (mahua and saaja), birds, animals (totemic emblems), and humans. Each subject is drawn in dot and line patterns and the overall design represents a uniformity of this technique. Each Pardhan artist has their own unique design. Some patterns are commonly used by everyone. However, some patterns are representative of a particular artist and certain design patterns are considered unique signatures of that artist. This distinction in signature designs is really important in the context of Gond paintings. For Jangarh Shyam – the dot and line signature was derived from the V-shape and dot form of tattoo drawn on the forehead of a Baiga woman. Nankusiya Bai (wife of late Jangarh Shyam Wife), after the Shyam’s demise, began using the same design to carry forward his legacy. Venkat Shyam, for instance, used lightning stones symbols found in Godna (body tattoo). Currently, he uses a semi-circle and dot that suggests supreme god and the 5 semi-circle that suggests 5 senses. His other pattern is black fibre, for which he got inspiration by seeing the fibres on the bark of a saja tree. Anand Shyam’s signature uses U-shape and lines. It was inspired from the moon in the night sky. The signatures fill up the space drawn on the subject and objects of each Gond painting.

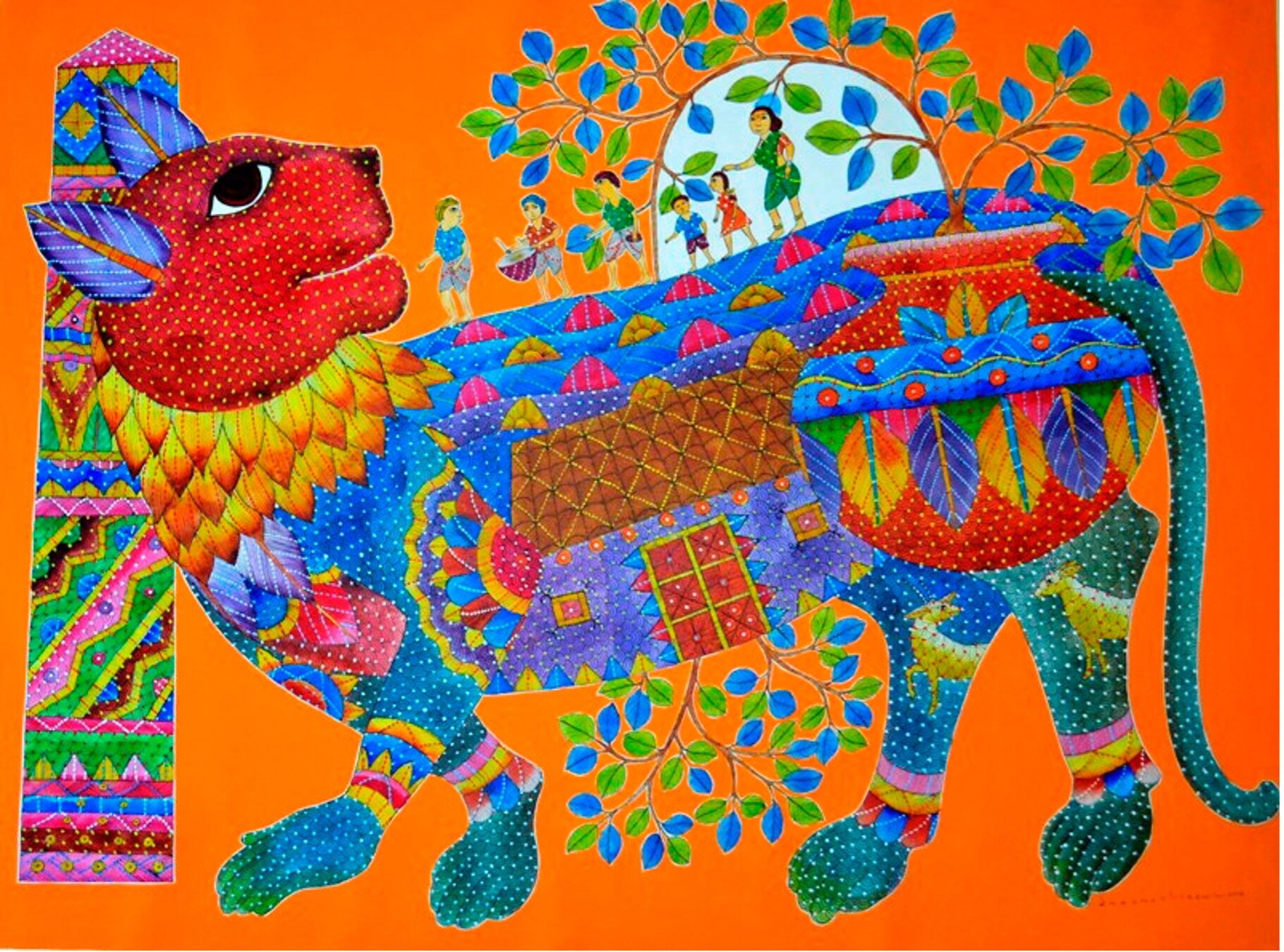

In the above paintings of Venkat Shyam, one can observe several elements of Gond community (birth, wedding, and death rituals) and its interconnected relationship with nature. It showcases distinct style of Venkat which connects different symbolisms and mythic characters and its sync with nature. The leaves represented here are used in Koitur wedding ceremonies to cover rectangular poles. The Baghdeo, tiger spirit, forms the core element of the painting and represents the belief of Koitur people which requires blessings of the spirit during wedding ceremony and other rituals. The wedding procession can be seen on top of Baghdeo, who takes care of everyone in the village, while the mud houses with tiles and doors are painted at the centre of Baghdeo. The wooden pillars symbolise wedding. While the pig, which is sacrificed to the Baghdeo in the procession and later becomes a feast, is drawn inside Baghdeo.

In 1975, while India was going through a declared Emergency, a multi-art complex Bharat Bhavan was conceptualised and finally opened in Bhopal in 1982. Jagdish Swaminathan was appointed as the first director of Bharat Bhavan, subsequently Jangarh Shyam started Gond art on canvas with the opening of Bharat Bhavan in 1982 and continued till his death in 2001. Sandeep K Luis, a researcher from Jawaharlal Nehru University, in his paper titled, ‘Between Anthropology and History: The Entangled Lives of Jangarh Singh Shyam and Jagdish Swaminathan’, argues that before opening of Bharat Bhavan, Swaminathan sent artists and students to explore unrecognised folk and Adivasi art. ‘With the assignment of collecting and documenting these art practices, and if possible, also to invite these Adivasi and folk artists to be part of Bharat Bhavan’s Roopankar project, one of the talent scouts reached Shyam’s Patangarh village in October 1981,’ he writes. Shyam was also a relative of British Anthropologist Verrier Elwin, who married two Gond women, including Shyam’s cousin Lila. Additionally, Shyam’s father was also Elwin’s house cook. After joining Bharat Bhavan, Shyam did menial jobs and worked his way up to become a studio assistant. By 1983-84, Shyam started painting on canvas with images of forest, trees, animals depicted with dot-painting technique and lines creating a unique art form. Jangarh style was inspired from the tattoos and body art of baigas.

Elwin remains one of the most influential British anthropologists responsible for tribal policies in Independent India. It has been argued that Elwin was instrumental in categorising Adivasis as Hindus, despite the fact that Adivasi communities practiced their own Indigenous religion, and he also supported Hindu group’s activities in Adivasi areas. Elwin has been widely criticised by the Gond community for his problematic stances on the community's youth dormitories, Gotul, which is considered as sacred institutions, and for using marriage with Gond women as a way of “getting to know the community better.”

According to Luis, by the late 1990s Shyam was facing deep financial vulnerability, in addition to physical and mental health issues. Amid this, in 1999, he accepted a residency programme at Japan’s Mithila Museum for meagre 12,000 rupees per month (roughly $160). ‘His three month-long stay at the museum left serious psychological effects on him, since it was located in a remote village and there was hardly anyone capable of communicating in Shyam’s language,’ Luis writes. Shyam, however, again took the same residency programme in 2001 and in letters to his wife, he communicated with her that he was made to work for 18 hours a day and was being cheated. Before his wife Nankusia could receive the letter, Bharat Bhavan was informed from Japan about Shyam’s death, who had reportedly hanged himself out of depression and anxiety.

In discussion with some Gond artists, they acknowledged and rued why he’d chosen to go thousands of miles away for a meagre salary. This brings into limelight the neglect, hostility faced by Adivasi artists in the upper caste dominated institutions of urban centres. Shyam’s death by suicide is a clear-cut example of how the most pioneering Pardhan-Gond artist was pushed to death in an exploitative art industry of non-Indigenous people.

The Pardhan artist and author Venkat Raman Shyam argues that art galleries and collectors see Gond paintings as contemporary art and it is rightfully so. ‘We are creating current subjects in the current time period,’ Venkat told me during an interview. ‘When I worked with Jagdish Swaminathan, once while looking at my painting, he told me, “Your painting is not traditional, it is contemporary”. And so we should not call Gond art traditional art, but consider it as contemporary art.’

Venkat further added that nowadays, everyone wants to do Gond painting as people think it is easy and not complex. It is because, he argues, ‘they are ignorant of the core values or philosophy of Adivasi culture.’ This also raises a significant question of appropriation of Adivasi Indigenous art in India. One can find several non-Koitur, non-Adivasi artists creating and selling Gond paintings online. In the absence of any legal protections for the art produced by Pardhan-Gond or the larger Koitur Adivasi community, it becomes easier for their works to be pirated and copied. The Indian law does not provide any such protection for Indigenous Intellectual knowledge system, except the provision of Geographical Indicators (GI) wherein a particular artist is given the legal rights to produce certain art. While some Pardhan painters, such as Venkat, have gotten GI recognition for themselves, the various Gond art forms – paintings, wood carving, and sculptures – are deeply vulnerable to piracy and misuse of their indigenous knowledge as non-indigenous people monetise over their art.

The Gondwana exhibition hostel by Adani was organised without proper consent of the people. The artists participating in this were very likely unaware of the sponsors. Venkat told me that Rajeev Sethi, a known art curator who has worked to promote Indian folk, traditional art, reached out to him to suggest names of Australian artists and offered to work with them. The project was later given to another Pardhan artist Bhajju Shyam who collaborated with Aboriginal artists from the Warlpiri community, represented by the artists Otto Jungarrayi Sims and Patrick Japangardi Williams. The project comes at a time when Aboriginal communities are resisting Adani mines in Carmichael in Australia, which is considered a sacred land by Wangan and Jagalingou people. Similarly, in the central Indian state of Chhattisgarh, Koitur communities are fighting against Adani coal mines and iron ore mines in Surguja and Bastar.

While it is wonderful to see two ancient, old Aboriginal communities coming together and working on a project to showcase their heritage and culture, there is more to this than meets the eye, the homelands of both these communities are being obliterated by the very sponsor of the Gondwana project. The Hasdev Aranya forest in Chhattisgarh’s Surguja is home of the Koitur people and is now under threat. It was previously a no-go zone and off-limits for mining because of the rich biodiversity and one of Central India’s most dense stretches of forest. As many as 30 villages – 420,000 acres of forest land – are at severe threat from Adani mines. Additionally, a way of life which respects and protects this forest is at threat, which people believe is being sacrificed for the growth engines of the economy. It is ironic, when the rest of the world is moving away from coal, the policymakers in India are auctioning coal block mines. Newspapers are filled with stories of corruption in coal block allocation (in fact, the previous government under United Progressive Alliance was brought down because of 2G and coal scam stories) but the lives and human stories of Adivasi residing on those lands remain elusive.

As the Koitur community stands fiercely on ground as gram sabha or village councils have refused to allow Adani to mine their land, similarly, Aboriginal communities are standing their ground against Carmichael mines in Australia. In this manner, the Gondwana project by Adani looks nothing more than a whitewashing attempt by Adani to hide its crimes and blood-tainted hands of human rights violations in Adivasi and Aboriginal territories.

Madhavi Uike is a Gond painter from Madhya Pradesh's Balaghat. She has written the essay of the journey of Gond paintings and it has been translated by Chandresh Meravi.