ILLUSTRATION: PAPERLILY STUDIOS

Coconut Candy

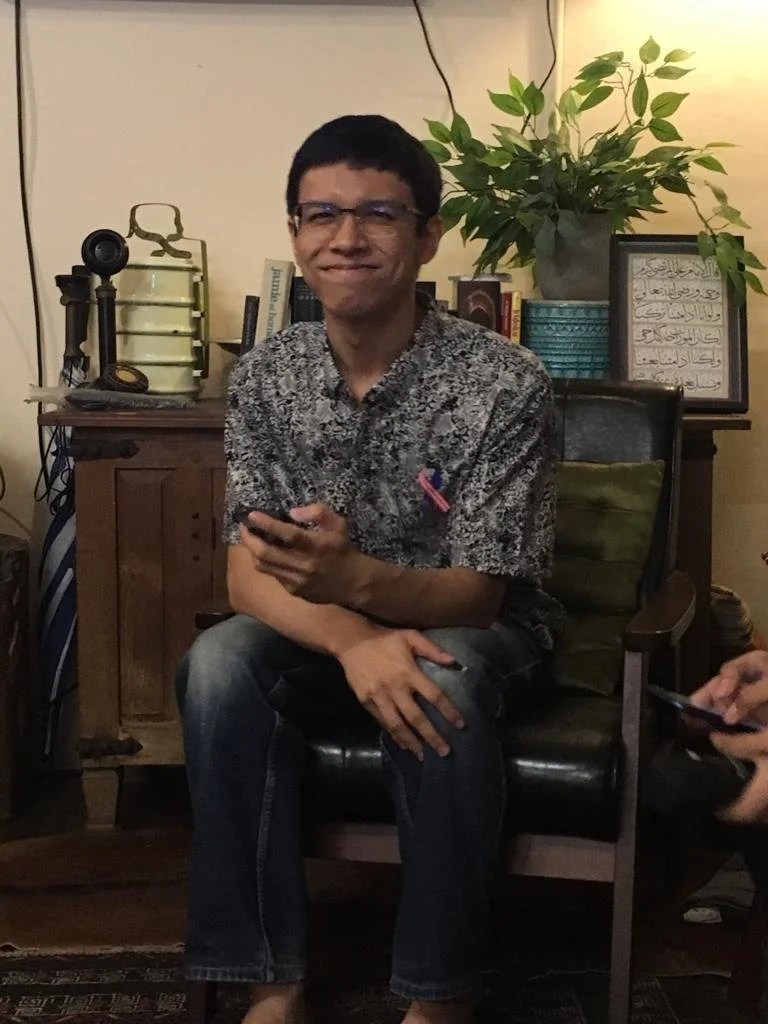

Adib Faiz

“What is patriotism but the love of the good things we ate in our childhood?”

- Lin Yutang

I sit in the University of Malaya’s lecture theatre, dismayed. I’ve been working on this assignment for about a week now, something called a ‘language autobiography’ charting my relationship to English. There’s a specific requirement to this final essay: we have to connect our personal lives to the broader academic discourse on Malaysian literature. So far– mounds of aborted first drafts, annotated copies of articles– and no progress whatsoever.

Failure is not an option; this is a core course. The deadline is the 7th of May. Today is the 6th.

Confusion has now morphed into anxiety; I hear myself screaming internally.

The screaming grows louder … and nearer. I spin round.

A man dressed in black hurtles toward me, leaving a trail of light. He narrowly misses me and crashes into the podium, beret askew.

‘WHAT THE–’

‘Still got it!’ the man says as he gets up, apparently unharmed. He presses his hands together, bowing flamboyantly.

‘Salleh Ben Joned, at your service.’

I stare at him in utter disbelief. ‘Salleh the Malaysian poet, journalist and satirist?’

‘And former lecturer at this university! It’s good to be back here, I have so many– what happened to the long wooden benches?’

He’s probably noticed the plastic seats with the flimsy tables attached, but I’m still astonished that the late ‘bad boy’ of Malaysian literature is standing before my very eyes.

‘Errr … errr, sir–’

‘Just call me Salleh.’

‘Well, Salleh, what are you doing here? How are you here?’

‘No time to walk you through it!’ says Salleh, as his terompak slip themselves back onto his feet. ‘I’m a literary construct, to help you relate your story to the ideas expressed by my contemporaries. Rokok?’ He offers me a cigarette.

‘I don’t smoke,’ I say, bewildered.

‘Suit yourself,’ he says, lighting up. ‘Now let’s begin. What language did you speak growing up?’

‘I spoke English, but– what is happening?!’

Salleh puts shredded coconut into a wok, which is somehow being heated by the podium.

‘It appears that I am making traditional coconut candy, popular in my hometown of Melaka. Clearly this is some kind of metafictional structuring device. Very postmodern. Keep talking.’

‘Well,’ I continue, ‘I come from a racially-mixed background, with Malay, Chinese, and Punjabi ancestry. Though our parents spoke to us in English, we used other languages in varying proportions. I addressed my grandparents in Punjabi, using the colloquial “Satsrikaal” rather than the formal “Sat Sri Akal”. We used Malay in religious classes, learning about “syurga dan neraka” and how to “ambik air sembahyang”. We also had an Indonesian helper, with words such as “bisa” and “kelmarin” entering my daily speech. The result was a patois unique to my cultural experiences, a form of English that integrated Punjabi, Malay, and Indonesian.’

‘This is why I disagree with Muhammad Haji Salleh’s attitude toward English,” Salleh says, adding sugar and Ideal milk to the coconut. ‘Muhammad positions English in relation to binary opposites: coloniser and colonised, foreign and indigenous, English and Malay. So it’s not surprising that he considered himself a “linguistic and cultural schizophrenic.”[i] Yet as your experiences demonstrate, cultural forces often coalesce into new entities. It’s like this candy,’ Salleh says, adding red food colouring to the mix. ‘For you, English is like the coconut at the centre, with other linguistic elements being added. Over time, a culturally unique base emerges, distinct from what came before but inextricably linked to it.’

‘I never thought of likening myself to candy,’ I say.

‘Did you go to a government school?’ Salleh asks, still stirring the wok.

‘Yes I did. The medium of instruction was Malay, but various languages were spoken.’

A flat tray materialises.

‘You must be on the right track!’ Salleh says. ‘Continue.’

‘Well,’ I say, ‘some of us spoke primarily in English or Malay. Those who had been to Chinese-medium schools knew Mandarin, but often spoke Cantonese. There were various Indian languages spoken, specifically Tamil, Malayalam, and Punjabi.’

‘The challenges of multilingualism!’ Salleh says. ‘I believe in embracing diversity, but I did regard this as a unique problem for Malaysian writers. We lack a certain unity and cohesiveness. Conflicting forces create multiple identities within the larger reality that we conveniently call “Malaysian” society.[ii] I wanted to find a Malaysian voice that embraced these multicultural possibilities; not as an ideological project – God knows I hate that sort of thing – but a simple and natural expression of what life is all about.[iii]

‘But that’s the interesting thing,’ I say. ‘In the context of my school, that Malaysian voice emerged on its own! Instead of producing communal pockets of language, my school became a crucible, fusing multiple languages into complex combinations. Our English was organically infused with Malay and Chinese words. The Head Prefect was “damn perasan”, we would “kautim” our homework, and the teachers might “rampas the UNO cards” if they were in a bad mood. Moreover, our Malay was heavily infused with English words. I remember asking a friend about her break-up, having only just heard about it. She responded with surprise: “Adib, you memang tak baca newspaper ke?”’

‘Most interesting!’ Salleh says, pouring the mixture onto the tray. ‘I suppose many of us, especially the Engmalchin poets like my friend Ee Tiang Hong, tried to forge a Malaysian voice through sheer force of will. Yet according to you, this voice emerged organically. I suppose this is akin to spreading coconut candy onto a flat tray. The mixture ultimately cools into a unique and highly textured form.’

Who knew candy could be an extended metaphor for amalgamation?

‘It was a government school though,’ Salleh says, conjuring a knife out of thin air. ‘I find it difficult to believe that the government encouraged cultural hybridity.’

‘Well there was the top-down instruction of Malay,’ I respond. ‘No one was against learning Malay, but–’

‘But you noticed what I did: that there was a huge gap between written and spoken Malay?’[iv]

‘Exactly!’ I say. ‘In order to pass our exams, we had to stay up-to-date with Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka’s latest spelling decisions. In some years, certain words were hyphenated; in other years they were not. We never knew if we ate goreng pisang or pisang goreng. There was a continual debate over the word for “air-conditioner”: was it penghawa dingin or pendingin hawa? Neither word was used in daily conversation.’

‘So in this environment of State control, English was expunged from Malay?’ Salleh asks.

‘On the contrary, the most flamboyant expressions came from English!’ I say. ‘Phrases such as “anjakan paradigma” and “langkah konkrit” were vital for doing well in essays. Rachel Leow asserts that Malay authorities unanimously dislike “pseudo-Malay words”, but that hasn’t been my own experience.’[v]

‘State language policies supposedly conserve the national language, the “soul of the nation”,’ Salleh says irritably, now cutting up the candy. ‘Yet this artificial adoption of English reflects state-led innovation, forging a “modern” language via bureaucracy. I suppose Wong Phui Nam’s comments regarding “national literature” also apply to language; attempts to control it for ideological purposes will ultimately produce dead objects.[vi] Compare the traditional candy I’ve made’– he puts down the knife– ‘with the machine-made coconut candy one finds these days. Is it efficient? Probably. But by flattening the mix with a mechanical press, the human touch– the soul of the work– is erased.’

‘But where does that situate my soul in relation to English?’ I ask, my anxiety returning once more. ‘And my assignment? Am I a native speaker of English, or a whitewashed Other? Should I consciously write in Malaysian English? Is such an endeavour artificial? Are– are you still listening?!’

Salleh is busy eating a piece of candy. He has already eaten three.

‘Makan lah!’ he says, handing me a piece.

I take a bite. A tranquillity comes over me, the flurry of concepts and arguments dissolving into nothingness.

‘What was your question?’ he asks.

I articulate my question calmly: ‘How do I sum up my thoughts regarding my relationship to English, in light of my experiences?’

‘Why think about that relationship,’ Salleh asks, grinning, ‘when you can taste it?’

Author’s notes:

[i] "Decolonization: A Personal Journey," 63-4.

[ii] Nothing Is Sacred, 52.

[iii] Nothing Is Sacred, 52-3.

[iv] Nothing Is Sacred, 55.

[v] Taming Babel, 223.

[vi] Writing A Nation, 57.

Works cited:

Joned, Salleh Ben. Nothing Is Sacred. Maya, 2003.

Leow, Rachel. Taming Babel: Language in the Making of Malaysia. Cambridge UP, 2016.

Salleh, Muhammad Haji. "Decolonization: A Personal Journey." Journal of Commonwealth and Postcolonial Studies, vol. 7, no. 2, 2000, pp.51-71.

Wong, Phui Nam. “Towards A National Literature.” Writing A Nation: Essays on Malaysian Literature, edited by Mohammad A. Quayum and Nor Faridah Abdul Manaf, IIUM, 2009, pp. 49-68.

Adib Faiz graduated with a double major in English and History with a first class in History from the University of Adelaide. Upon returning to Malaysia, he worked as an educator and researcher, becoming increasingly involved with media work in the process. Adib has also organised multiple intellectual and cultural events, and is a published author on academic and public platforms. He is currently a freelance screenwriter, copywriter, and copyeditor, and is pursuing his postgraduate degree in English Literature at the University of Malaya.