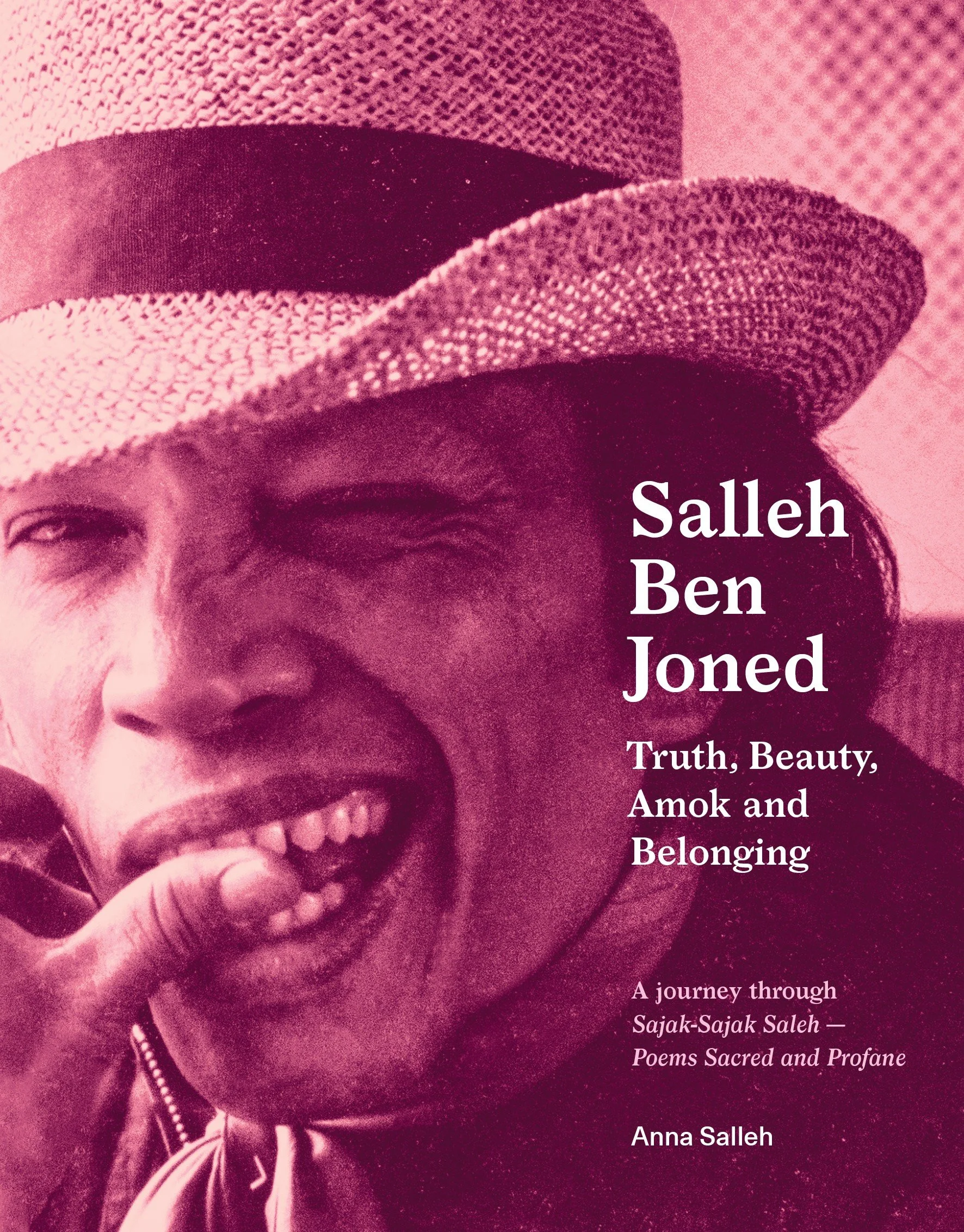

Salleh Ben Joned (left) and Wong Phui Nam (right) in 1992. Photo courtesy of Kee Thuan Chye.

Wong Phui Nam on Salleh Ben Joned

by Anna Salleh

— —

ABOUT SALLEH BEN JONED

Salleh Ben Joned (1944-2020) was a noted Malaysian poet and public intellectual who came to Australia as a Colombo Plan scholar in the 1960s and stayed for 10 years. He began at the University of Adelaide and later moved to Hobart to study English at the University of Tasmania under poet and literary critic James McAuley. When he returned to his home country, Salleh became known as a poet and columnist who delivered playful and well-read provocations on complex subjects such as race and religion. His brutal honesty and refusal to toe the establishment line meant that he was not officially honoured during his life as an important figure. Following his passing in 2020 however, the Malaysian press dubbed him the nation’s “uncrowned poet laureate”. Since then, there has been growing recognition of his contribution from those in the world of arts, literature, and academia. His legacy on younger generations of poets, writers, artists, and scholars is also becoming increasingly felt.

ABOUT WONG PHUI NAM

Wong Phui Nam (1935-2022) was a pioneering Malaysian poet and literary critic. His seminal works of poetry include How the Hills Are Distant (1968), Ways of Exile (1993), and Against the Wilderness (2000) along with two plays Anike (2005) and Aduni (2006). In the early 50s he was involved in The New Cauldron, one of Malaya’s first publications of poetry in English. As a student, he was encouraged and mentored by Wang Gungwu at the University of Malaya (now National University of Singapore) to pursue his literary ideals. He later moved to Kuala Lumpur to work in finance. After the National Cultural Policy in 1971, many of his peers left the country as they no longer felt welcome as Malaysian writers. Phui Nam himself stopped writing for almost three decades. For Phui Nam, the richness of culture and tradition are inherent in the languages that we write in. His final unpublished works are now being collated into a posthumous collection.

— —

It's 2019 and I am in Bangsar, Kuala Lumpur ordering coffee ahead of an interview with the late poet Wong Phui Nam. When I come back to the table, Phui Nam is doing Tai Chi. "I believe that chi is the link between the physical and the mental," he tells me.

I was in Bangsar to talk to Phui Nam for my ongoing research project on the literary legacy of my late father, the poet and public intellectual Salleh Ben Joned. In the 1990s the relatively softly spoken Phui Nam and somewhat louder Salleh had both been columnists for the New Straits Times' English-language literary page. Phui Nam had noted in 2003 that "more than anyone else" Salleh contributed to the rapid success of the page -- thanks to his "wit, ironic humour, biting criticism, the rare capacity to entertain and verbal vigour". At the same time, though, Salleh felt cast as a "cultural apostate" for his criticisms of the literary elite of modern Malaysia.

As the coffee arrives, I am struck at how frail yet calm Phui Nam appears: I was honoured he'd made the effort to go out and meet me in person. Before the coffee we had met up at the famed Silverfish Books, which was a precious outlet for writers like him and Salleh. I try to imagine how such outwardly different personalities would have got on during the 90s. Phui Nam explains to me that on a personal level he never got too close to the "outspoken" Salleh. "I never called him because I didn't know what kind of mood he was in and how to speak to him," he said. "When he was in a good mood, he was very exuberant. It was a bit hard for me to handle." But the two columnists did develop a respectful collegial relationship over time, with Phui Nam writing the introduction for Salleh's books of essays, Nothing is Sacred.[i] He says to me, "I appreciated him as a person."

While there are those that found my father insensitive, Phui Nam confessed that he enjoyed Salleh’s forthrightness: “He spoke the truth… He called a spade a spade and people didn’t like it”. Phui Nam explained that he shared Salleh's concerns with the impact of "bumiputera-ism" on the development of literature in Malaysia. The privileges that came with government patronage of bumiputeras had resulted in a closed minded and defensive literary elite that lacked humour, wrote Phui Nam in a 2021 retrospective on my father. Language was also "wilfully misused" by the elite to support "narrow unaccommodating religious, racial or cultural ideologies." This was something Salleh challenged in his columns.

In contrast to other Malaysian writers at the time, Salleh did not give up writing in English once Malay was deemed the language of national literature, Phui Nam says to me. "Salleh had his integrity and did not conform, therefore they think he is a rebel." He suggests that there were unsuccessful efforts to shut down the English-language New Straits Times literary page: "Malay writers were quite vociferous in attacking us."

While Salleh’s critics had branded him a traitor to his own race, Phui Nam tells me that my father loved "the good things in Malay culture – such as eating the food that he liked in his childhood". They both agreed that there was much to be celebrated in traditional Malay writing. "Texts like Sejarah Melayu are beautiful in their simplicity and it's a pleasure to read texts like that... and as Salleh said, pantuns had a lot of humour and liveliness."

Salleh's commitment to his religion was also put to question, but Phui Nam argued that Salleh was a "truer Muslim" than most of his critics. Phui Nam, who himself converted to Islam when he married, believed religion was about knowing "the divine presence" rather than adhering to rituals (Salleh's poem "Haram Scarum" comes to mind here). "[Salleh] was not against Islam," he insisted, "but against people who did not practice Islam as a means to find God ... only Islam as a code of conduct to beat others on the head with — in that I'm more holier than you — that's what he was against."

The purveyors of fake piety were a problem in many ways for writers like Salleh and Phui Nam: "They had sanctimonious attitudes towards things like sex," exclaims Phui Nam. While some saw Salleh as vulgar and were offended by poems such as “The Woman Who Said Yes”, Phui Nam argued Salleh was just stating the truth as he saw it. "'The Woman Who Said Yes' is a tremendous poem" and a "powerful statement implying that sexual ecstasy shades into mystical ecstasy," he insists. As one of the judges of the 1995 NST-Shell poetry competition, Phui Nam also praised another of Salleh's poems that dealt with matters divine: 'Adam's Dream in His'. His report on the poem, which won top prize, said it was “conspicuously superior” to the other 1,680 entries in the competition, stating outright:

[The poem] is a mature examination of the complex issues surrounding divine creation and human creativity, how the two are linked, and how the latter mirrors the former. It does so with economy of style, simplicity of language, and wit... the poet refuses to set himself up as an authority on either religion or poetry. Yet, it is clear that Salleh has pondered deeply on these two facets of human life.

Salleh’s prefacing of ‘Adam’s Dream in His’ with a quote from John Keats concerning imagination, beauty, and truth speaks to his love of the poet.

I am certain of nothing but the holiness of the Heart's affections and the truth of the Imagination – What the Imagination seizes as Beauty must be truth ... The Imagination may be compared to Adam's dream – he awoke and found it truth.[ii]

Phui Nam went so far as to say that Salleh had been unparalleled among Malay writers. His position afforded him a penetrating voice that was used without fear: "Being Chinese, I wasn’t in the position to write as he did... Salleh couldn’t be accused of being racist [in his writings] because he was a Malay himself."

And what did Phui Nam think of Salleh’s most infamous act, publicly urinating in protest at Redza Piyadasa and Sulaiman Esa’s 1974 art exhibit Towards a Mystical Reality held at Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, Malaysia’s National Institute of Language and Literature? "Maybe he went a little bit too far there," laughed Phui Nam, who was at the same time intrigued at the importance placed on this “pissing incident” by contemporary scholarship. Along with Salleh’s notorious ensuing essay The Art of Pissing, academics and art historians have come to regard this act as an important moment of critique in the field of Southeast Asian art.[iii]

In his 2021 obituary for my father, Phui Nam noted that decades on, Salleh's writings were still relevant to many issues facing Malaysia today: "We need a growing majority to speak for the truth even if it is just among ourselves."[iv] Not long after he wrote this, Phui Nam himself passed away. Yet while we have now lost both these great men, their poetry and prose lives on. And as I write, it is evident that their passion for speaking their truths continue to live on in a younger generation of Malaysians and beyond.

Author’s notes:

[i] Phui Nam's Introduction to Salleh's book of essays Nothing is Sacred (Maya Press, 2003)

[ii] Keat’s quote is originally from his letter “The Authenticity of The Imagination” to Benjamin Bailey written on November 22nd, 1817, on religion and imagination.

[iii] “The Art of Pissing” in As I Please (Skoob Books, 1994); recently reprinted in The Modern in Southeast Asian Art: A Reader, edited by: T.K. Sabapathy and Patrick Flores, National Gallery Singapore and NTU Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore, 2023

[iv] Phui Nam's obituary for Salleh in MMOJ, 1 June 2021. Available: https://menmattersonlinejournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/21-Wong-Phui-Nam.pdf

— —

A new publication forthcoming November 2023 from Maya Press:

Salleh Ben Joned - Truth, Beauty, Amok and Belonging

SALLEH BEN JONED. Poet. Critic. Dramatist. Legend in his own lifetime. With a strong sense of the absurd, Salleh playfully challenged taboos on race, religion, language and identity, all with brutal honesty. In both English and Malay, he celebrated the mystical, the sensual, the beauty — and terror — of life itself. He pushed beyond conformist boundaries and paid the price. This book shines a spotlight for the first time, via his poems, prose and relationships, on the world view of Salleh Ben Joned.

Anna Salleh combines a passion for journalism and music. In her long-standing association with the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, she has been an editor, journalist and producer, creating online articles and podcast documentaries on everything from science, environment and Indigenous issues to ethics, music and social history. She is also a seasoned singer, guitarist and songwriter, and has traced her journey of musical discovery in the audio documentary Brazil Calling. In a 2020 ABC podcast series Salleh Ben Joned: A Most Unlikely Malay, Anna provided a moving two-part exploration of the provocative life of her late father. She is now completing a new book on Salleh due out in November from Maya Press. Subscribe to Salleh Ben Joned's Facebook Page and check the SBJ Blog for updates on the book and other SBJ literary legacy projects.