Against the Wilderness

Wong Phui Nam

First published by Blackwaterbooks, 2000. Recordings by Brandon K. Liew, 2022.

For Daizal Samad, who knows about migrations.

— —

i

Antecedents

For months, the sky was pale copper, withholding rain,

firing the fields into fused beds of clinker.

A subterranean kiln reduced standing grain and grass

to fibre, snakes and mudfish in their holes to bone.

When people turned from eating bark to sand, we waited

for our dead to putrefy before we buried them.

Then we left. Every unseasonable road we took

brought us among other aimless ghosts in a treeless,

unforgiving plain, crying like us against exhaustion

of spirit as our bellies ate us from within,

making our bones come unjointed. Nursing with paps

blackening from the teats, I was death for our howling son.

In the city, we gave him up that we might eat.

Though we were ghosts, we found it very hard to die.

— —

ii

Bukit China 1

So long of the sea, I became its aborted creature

dropped from the land, from the soil of rooted community

bled to a shocked exhaustion. Wasting into a numbness

that grew malignant as an unease eating into bone,

I came adrift. In time, I shed the stink of loess

in waters that turned corrosive under an open sun

and, naked, caught the desolation of an empty quarter.

Much as others cribbed with me between the ribs

of a derelict junk set loose upon the seas,

I became a stranger beast than any for having still

remnant of a human face, healed into the pack

that ravaged these peopled waters. Chopper in hand,

I worked through ribcage and skull, through settled breeding men

as I would shake from me this pain, this abandonment by spirit.

— —

iii

Bukit China 2

When my sea-blackened junk crumbled for its weight

of salt-gutted timber as it sat dry on a spit

of mud, I gave myself over to the thought

the sea had retched me up for final dissolution

in the waiting earth. In the flesh, I sensed the flood

gathering in the soil already of lapping oblivion.

From these small hills, I had no unknotted wood to remake

myself my sundered craft, in a city somnolent still

as mangroves fecund in sea-snakes, in mudskippers,

scarce hint of an architecture for vessels by which

our fathers through the ages flouted the blackest, boiling seas.

My flesh would find continuance in the moist salt wombs

of native women and leave secreted into this hill

a clutch of bones from which no transfigured life would hatch.

— —

iv

Arrival

The sun itself seems to nestle in the harbour,

making liquid mirrors of the water between ships

glowing at anchor, rust red. Even the wharves have come

alight, intense, lime-white, for being combustible.

Through a haze of oiled sea smells, they sear the eyes.

A little beyond, the houses burn, bricked and closed in –

ovens to bake humanity not out in the sun.

Language here turns gibberish, resistant as brown earth,

as raw green scrub that over it senselessly runs.

What people are these? Boatmen, coolies, demons,

flotsam on the tides that have flooded over the edge

of the netherworld? I saw that coming in,

jungle pouring out of mountains into the sea’s mouth,

holding the world’s gloom, its inhospitable spirit.

— —

v

Into the wilderness

When the valley dawned about us, we sensed

that we had come, each to our particular end.

We found ourselves detached as shadows at the mouth

of a great receiving darkness. So far inland,

we lost the clarity of the day’s fires,

the luminescence of pain as the sun broiled

us in our skins when we poled our way upriver, hearts

locked tight on a single lust – the glittering image

of life we would retrieve in our waking dreams

from sands beneath watery mirrors that blinded us

by day, flowing by night as cold thoughts of death.

In that we were into the hills for other than a god,

he came, blind knobs for eyes, swelling gourd for belly,

crying out of the water for our lost, drowned selves.

— —

vi

Mining the earth

We maimed the vitals of the jungle in deep earth,

hacked and rooted up, bole and vine, its ferocious dream

of life in the massed green of the grappling vegetation.

Caring little for such spirits as would haunt the ground,

we put it all to fire to open up a gaping trench

of acrid, cindery netherworld that choked the sky.

As if we had to descend into a further darkness

that we might grub for its heavy ore amidst burnt ruins,

we worked the charred ground into an open flooded pit –

a maw, wet and receiving of our ignorant flesh.

For it was the earth that took from us, burning

with fevers from its breeding waters our dreams off us.

We were the ones to relinquish, with our bones,

our flesh, give it all back to the digestive earth.

— —

vii

China bride

From my first bright flow of blood, I caught the sea-scent

I carried of the fecund belly-heaviness of bitch

and sow. In open day I was almost light as flame,

smouldering magnolia touched off by late winter rains.

I was such as smoked the senses of boys and men till

they, wallowing in their secret sty of thought, fed

wasting on my flesh attained, yet never attainable.

I was sent for then, bought bride to help him into breeding

flesh, into sweaty forgetfulness of darkness he disturbed

on spirit-infested jungle rivers concealing ore.

But he never found me even as he rifled, sieved

my body, smelling out crotch and underarm and drugged

himself on the bitter exhalations of my woman’s glands.

He burrowed, a fly into carrion, to seed me with his death.

— —

viii

Second generation

The streetlamps feed off darkness in this neighbourhood

to fuel a low spirit burning out in small pools of light.

Day reveals its traces worked into the wood rot

of our subdued, lime-washed houses. In hot interiors,

we swell on the juices of our small immediate griefs,

becoming monstrous as pupae subsisting on a mess

of white pulp and so grow fat in the secure

and confined air of a nest of somnolent cocoons.

We emerge with the instincts and the smell of generations

of deprived forebears bred from us. So changed,

we lose the fear of demons by whose governance we live

and so think it right to take to their ways and learn

to speak and mouth the syllables of their tongue,

babbling, in time, even of green fields, of golden daffodils.

— —

ix

Admonishment against the city.

When you have dried out from the caul of common sleep

of creatures, you will know awakening is

a breaking out, a hatching of the spirit

onto time’s dangerous, unending wastes.

The city, for you, reveals itself as desert.

Under a bright pall of heat that fires every street,

you will pick your way in and out of the dreams

of sleepers. Be wary, for you must know your way

about their gardens, offices and malls. Under their fat,

transplanted palms, in houses of many rooms, do not

find fruitfulness in yourself as flesh in dream,

or dream working itself out as flesh. Sleepers

will have bread from stone, be their keepers, like them,

test the will of cunning angels from high roofs.

— —

x

Hunting boar

Trekking into these hills, we lost trace

of our selves and the count of days,

drifted into a waking reptilian dream

of swamps and jungles. The sun it

hung snagged in the vines of massed voracious trees.

We have not had centuries here. And yet…

It was perhaps an after-light of rain,

mist gathering, becoming high ground:

a stony barrenness such as that

which generations had set their hearts upon.

We caught momentary sight of their winter pines,

their heaven-haunting cranes… And worn steps

trailing up an immensity of bald crag into stillness

that has nothing of the world, of dream, of time.

— —

xi

Memory

‘Returning by night to Lumen’ – Meng Haoran

The distant temple drifts on the sound of its great bronze bell

as it beats against the darkness closing on the hills

against a gathering uproar at the ferry

where many would cross while a little light remains.

At the further bank, small humanity wanders

over sand spits, making for low homes at the water’s edge.

I too will chance the currents for a crossing

to Lumen where all the woods will be white tonight

with the moon on fire, ice-bright in the rising mists.

Home is where the secret place of the ancient, Pang Gong, is.

Through pine and barren rock, a faint trail thins out

at the edge of desolation where the high bald crags begin.

Only the solitary comes and goes here, lightly,

done with a self that lusts unceasingly after the world.

— —

xii

A field not mine

This is a field not mine, fecund with new spawn,

cold blooded life. In that mood of year of dense rains,

it spreads itself, darkly subdued, into an acre

of day’s glass shadowy with fish. In the pale

rot of stubble, soft incipient crabs forced up

with the broth from swamps take form, waiting

to swarm as a mass of grey gel from the mud,

as midges appear out of the heat and moist, ripe air.

In this figure of the field, uncertain lights

over the far bund may signify phosphorescences not

of fireflies but bright entrails of spirits hungry

out of the earth to comb the night for frogs and snails

and raw small life. Yet in darkness most profound

beneath the flooded field, not mine, the dragon stirs.

— —

Epilogue

After ‘The Sunset of Romanticism’ – Charles Baudelaire

How beautiful the sun is, rising fresh and clear,

a bursting round of light that sends forth the morning’s joy.

Yet happy is the man who can, with love, reach out

to receive his dying glory brighter than dream.

I remember, and have seen all – flower, spring, furrow

grow faint under his eye like a heart softly beating.

We make for the horizon then. It is late. Run

to catch one beam at least of the declining light.

In vain I pursue the god who conceals himself,

and irresistible night now has full dominion

here, where it is dank, lightless, foul, and full of fear.

An odour rising from the grave poisons the dark,

and by the swamp’s edge, in trepidation, I step on

and crumple unexpected toads and slime-cold-slugs.

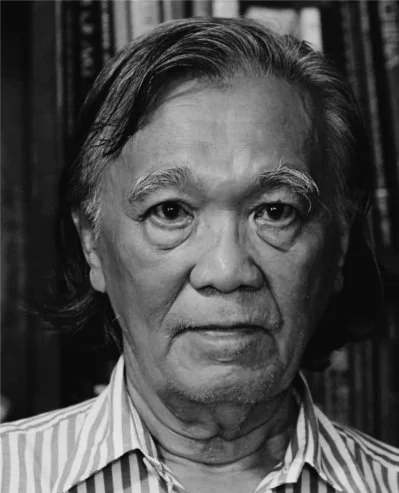

Wong Phui Nam (1935-2022) was a pioneering Malaysian poet and literary critic. His seminal works of poetry include How the Hills Are Distant (1968), Ways of Exile (1993), and Against the Wilderness (2000) along with two plays Anike (2005) and Aduni (2006). In the early 50s he was involved in The New Cauldron, one of Malaya’s first publications of poetry in English. As a student, he was encouraged and mentored by Wang Gungwu at the University of Malaya (now National University of Singapore) to pursue his literary ideals. He later moved to Kuala Lumpur to work in finance. After the National Cultural Policy in 1971, many of his peers left the country as they no longer felt welcome as Malaysian writers. Phui Nam himself stopped writing for almost three decades. For Phui Nam, the richness of culture and tradition are inherent in the languages that we write in. His final unpublished works are now being collated into a posthumous collection.